Brent Powers

Lieutenant, U.S. Navy

Introduction

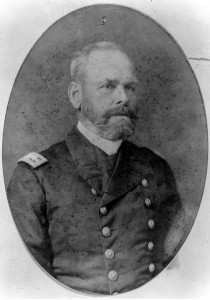

Figure 1: Adm. Samuel J. Locklear III, commander of U.S. Pacific Command, has charged his officers with thinking about how they will show up to the next war and be lethal and dominant. Here he briefs the Pentagon press corps on America’s rebalance to the Asia-Pacific region. (U.S. Marine Corps photo 140123-M-EV637-053)

As the U.S. military finds itself several years into its rebalancing to the Pacific, with an unspoken focus on China, today’s naval officers would recognize the conditions that their pre-World War II forebears faced. At that time, “the possibility of a war with Japan dominated U.S. naval planning… The U.S. Navy spent the interwar period trying to solve the operational problems associated with a trans-pacific naval campaign.” 1 A tight fiscal situation meant “research on new technology took second place to maintaining and improving existing equipment,” 2 while its probable enemy “sought to improve the quality of its fighting forces to offset the U.S. Navy’s quantitative superiority.” 3 Substituting China for Japan, conditions today are much the same. In trying to determine what lessons today’s planners can draw from the Pacific War, the guidance of the current Commander, U.S. Pacific Command, Admiral Samuel Locklear, provides one starting point. He recently challenged his current generation of surface warfare officers with “thinking in the offensive mode… how are you going to show up, how are you going to be dominant, how are you going to be lethal… to think about all scenarios, not just the ones…where we have enjoyed the basic air superiority, basic sea superiority.” 4 The U.S. submarine campaign and the surface naval battles in support of the Marines at Guadalcanal each inform the most important lesson for today’s planners: that the best plans, doctrine, and training formulated before the conflict will likely fail during execution. Commanders should expect that failure, identify its root causes, and take aggressive action to correct them. The American submarine fleet’s performance over the course of the war shows one way to overcome initial unpreparedness in order to conduct offensive operations, while the Allied surface fleet’s lackluster performance in night action at Guadalcanal demonstrates what happens when forces arrive to the sort of fight they do not expect and fail to adapt to it.

The Submarine Campaign

Figure 2: USS Tarpon (SS-175) recovering a practice torpedo, during exercises off San Diego, California, 22 August 1937. Prewar torpedo exercises failed to the reveal flaws in warshot torpedoes that would become evident early in the war.

(Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 63184)

The war that the U.S. submarine force waged in the Pacific offers a case study on the importance of matching one’s means to strategic ends. Although the world had seen the powerful effect that submarine raiding against commerce could have during the First World War, a number of international treaties during the interwar period forbade this sort of unrestricted submarine warfare. Indeed, just prior to World War II, Benito Mussolini used the Italian Navy’s submarines to support General Franco in the Spanish Civil War by sinking both belligerent and neutral merchant shipping. Enraged, the British, French, and Soviets came together under the Nyon Agreement to patrol the Mediterranean and sink all suspect submarines. Even before the patrols began, the international pressure forced Mussolini to abandon his undersea campaign. 5 Nothing during the interwar period suggested that the international community became more comfortable with use of unrestricted submarine warfare against commerce as World War II broke out.

For decades, the U.S. Navy had envisioned an economic blockade of the home islands in its planning for a war against Japan. Under this framework, the leap to accepting unrestricted submarine warfare matched strategic ends to the U.S. Navy’s available means. War Plan ORANGE called for an economic blockade of Japan, albeit by the surface fleet under the rules of cruiser warfare. 6 After the attack on Pearl Harbor, America found itself in a war against Japan, but without the surface ships or advance bases it needed to conduct a blockade. While it would acquire both over the course of the war, it still had its submarine force from the start. The decision to use unrestricted submarine warfare reflected the pragmatic realities and was “coolly, studiously strategic.” 7 As Holwitt concludes, “unrestricted submarine warfare carried a great deal of moral and legal baggage, but for naval war planners, the strategic necessity for unrestricted submarine warfare dovetailed with over thirty years of U.S. naval war planning.” 8 Although some submarine officers, including Hyman Rickover, “recognized the efficacy and probability of unrestricted submarine warfare…doctrine and training ignored their pragmatic opinion.” 9

Nevertheless, in the interwar period, American naval planners considered the submarine’s “most important employment [to be] in operations against enemy capital ships, and until that type of operation was reduced in its importance to the general employment of naval forces, [they] would not contemplate using submarines against commerce.” 10 In fact, the U.S. Pacific Fleet’s commander in 1936, Rear Admiral Reeves, commenting on likely missions of his submarine force in a war against Japan, opined, “the primary employment of submarines will be in offensive operations against enemy larger combatant vessels…No submarine will be assigned in the early stages of the war to operate against enemy trade routes.” 11 Given the expected primacy of the battleship in naval warfare and the previous history of submarine employment, the American planners made reasonable assumptions about the limited role their submarines would play.

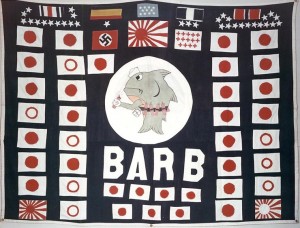

Figure 3: Battle flag used while Barb was commanded by Commander Eugene B. Fluckey, circa 1945. One of the best examples of how successful an aggressive submarine commander could be, Commander Fluckey took the fight to the Japanese, even sending men ashore on the Japanese home islands to blow up a train. (Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 63789-KN)

American submariners developed doctrine for the sort of warfare that their strategy prescribed and international law permitted. They practiced penetrating anti-submarine screens and conducting submerged torpedo attacks against enemy capital ships, the sort of training that could have produced aggressive skippers who would have made short work of unarmed, unescorted merchant ships. Nevertheless, overestimation of the anti-submarine capabilities of surface ships and aircraft inculcated an overabundance of caution in submarine commanders that “constituted a significant obstacle to the use of the submarines as a strategically valuable weapon.” 12 Submarines that operated submerged, but with their periscopes just a few feet out of the water, could better evade the anti-submarine forces they feared. However, doing so reduced those submarines’ search radius to just a few miles. Further compounding the situation, the United States’ torpedoes suffered from faulty detonators and miscalibrated depth settings that hindered efforts to sink the targets its submarines did find. Once the Chief of Naval Operations issued his order for unrestricted submarine warfare against the Japanese on December 7, 1941, the American submarine force found itself using “false [tactical] lessons learned in peace” 13 with underperforming weapons to carry out a strategy its commanders had rejected before the war, and one that might be illegal under international law.

The submarine force’s lackluster performance throughout 1942 and 1943 forced its leaders to recognize that its prewar doctrine was failing. Extracting relevant lessons and tactics from the patrol reports of successful skippers, the force’s top leaders urged more aggressive action to little effect. By the end of 1943, the Navy’s Bureau of Ordnance had fixed the technical problems with the torpedoes, while detailed intelligence of Japanese merchant ship movements provided by the U.S. Fleet Radio Unit Pacific aided submarines in finding targets. Nevertheless, “even with this intelligence support…submarine commanders using prewar concepts of operations had serious problems finding merchant ships.” 14 In order to get away from those prewar tactics, the submarine force swapped its underperforming commanders by relieving those who failed to sink enough Japanese ships over the course of two war patrols. While senior leadership used tactical bulletins to recommend aggressiveness and best practices, the character of the submarine skipper became the most important factor for success. The force needed commanders who took the initiative, thrived in a decentralized command structure, and possessed “emotional stability and daring.” 15 With “no satisfactory technique… ever found…to identify the right kind of men for submarine commands,” immediately removing those who were not performing became the best option. 15 Ultimately the submarine fleet took almost two years to transform into the lethal force responsible for the destruction of the Japanese merchant fleet, and “by the time the American submarine fleet was finished with their economy, the Japanese no longer had the capability of waging offensive warfare.” 17

Some might argue that the submarine force did a poor job of adapting its performance and that its success stemmed from combining intelligence on merchant ship schedules and tracks, derived from highly classified signals intercepts, with fielding reliable torpedoes, since the submarine force’s attempt to send feedback to its commanders through war report endorsements and Tactical Bulletins were considered ineffective. 18 In this case, having submarines properly positioned and equipped with effective weapons would make success against merchant shipping largely independent of the submarine commander’s mindset. Indeed, once commanders had good intelligence and a reliable weapon by the end of 1943, the rate of sinking Japanese merchants rose dramatically. However, the best intelligence that the submarine force had would not be effective without capable commanders who understood the nature of their submarines (possessed coup d’oeil in Clausewitzian terms). The ability to take risks and decisive action in order to locate Japanese vessels, even on the basis of precise intelligence, proved the decisive factor. Based on submarine technology at the time, intelligence could put submarines in the right area, but their skippers still had to operate properly in order to find, fix, and target the merchant ships.

Lessons for Today

Prewar planners can devise strategies based on the best intelligence they have at hand, but as Clausewitz argues, “the very nature of interaction is bound to make it unpredictable. The effect that any measure will have on the enemy is the most singular factor among all the particulars of action.” 19 Doctrine and strategy formulated during peacetime against a notional enemy may prove ineffectual against actual enemies who have conducted their own planning and have their own capabilities. Senior leaders should expect that parts of their untested strategies or tactics will fail, and they should be ready to shift to new ones, even without any guarantee of success. Although the submarine force could not empirically determine what made some commanders better than others, it could identify successful ones and remove those who were not. Today, Admiral Locklear sets a high bar of expecting his units to show up to a conflict lethal and dominant; but in the event they do not, evolutionary adaptability to whatever works, be it commanders, tactics, or a certain technology, offers a proven path to success.

Night Naval Battles at Guadalcanal

In the interwar period, most thinking about how to fight a Pacific naval war centered on the use of battleships

as the best way to transport firepower across the Pacific Ocean and bring it to bear upon the Japanese fleet. Only the battleship had the endurance to sail across the ocean under attack from Japanese airplanes, submarines, and cruisers and, at the end, be ready to meet the enemy fleet in a second Jutland. A battleship’s long-range heavy cannon could shoot farther than a torpedo, and its shot fell more accurately than a bomb. 20

Although the American fleet modernized throughout the 1930’s as its air, surface, and submarine forces brought new capabilities and weapons on-line, the United States focused on preparing for a decisive surface fleet engagement with the Imperial Navy. Japan, too, had a “supreme faith in the decisive fleet engagement as the ultimate arbiter of naval power.” 21 Since the Washington Naval Agreement limited the number and tonnage of capital ships each nation could construct, Japan was forced to develop asymmetric tactics for its cruisers and destroyers that would attrite the American fleet before the ultimate showdown. Indeed, the Japanese Navy General Staff spent much of the 1930’s studying night combat and developing doctrine and technology, such as optical devices, so that “by the end of the decade, the Japanese navy thus had more powerful, more effective, and more dependable night fighting equipment than did any other navy in the world.” 22 These advances made the Imperial Navy more ready than the U.S. Navy for the night fighting at Guadalcanal.

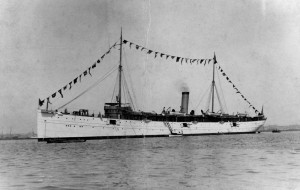

Figure 4: A U.S. destroyer steams up what later became known as “Iron Bottom Sound”, the body of water between Guadalcanal and Tulagi, during landings on both islands, 7 August 1942. Savo Island is in the center distance and Cape Esperance, on Guadalcanal, is at the left. Photographed from USS San Juan (CL-54) from a location approximately due east from the northern tip of Savo Island. (National Archives, 80-G-13539)

American tactical development, driven by an expectation of a decisive fleet engagement, failed to anticipate Japan’s likely tactics from its history, even though the U.S. Navy recognized the threat that the Japanese posed at night. Even a cursory study of Japanese naval combat since the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1985 would reveal that the Imperial Navy had favored night attacks in prior wars, as evidenced by the night raids on Weihaiwei harbor in February, 1895 and the attack on Port Arthur nine years later in the Russo-Japanese War. The Office of Naval Intelligence reported on Japanese night combat training, while the U.S. Naval War College’s tabletop war games demonstrated how effective night attacks could be. 23 Still, the Americans’ preparations for night combat suffered from “mistaken assumptions about the nature of the upcoming war…[and] failed to provide for the strategic situation the navy encountered.” 24 Despite the warning signs, the chimera of a decisive surface fleet engagement drove an emphasis on the tactics of major fleet battles at the expense of minor actions, such as the ones fought at Guadalcanal. The U.S. Navy did exercise night search and attack tactics against enemy battleships as a prelude to the decisive engagement 25 and “night battle practice was an extremely important exercise” 26 in the interwar period. However, the Americans conducted this training in the context of a major fleet engagement and never “simulated the ‘Minor Tactics’ that dominated the battles off Guadalcanal.” 27 Thus, the American fleet remained unprepared for the sudden, close-range, and confusing mêlées that characterized these actions.

The results of the first night battle between surface forces of the Guadalcanal campaign, the Battle of Savo Island, revealed the mismatch in night fighting capabilities between the two fleets and should have offered an object lesson for the Americans. During a night attack, the incoming Japanese column evaded the Allied destroyer pickets and attacked two forces in succession, sinking four cruisers and one destroyer, while suffering limited damage in return. With some pickets even ignoring the approaching Japanese warships, the Allies failed to recognize that the Japanese were nearby until after the attack started. Then, poor communications prevented the pickets from warning the rest of the force that an attack was underway. This battle marked Japan’s most lopsided nighttime victory over the Allied surface force during the Guadalcanal campaign. The Japanese owned the night. They used it to ferry troops and supplies to the island, and to attack both the Marines onshore and patrolling naval forces for months.

Later engagements in October and November off of Guadalcanal and Tassafaronga resulted in heavy American tactical losses during night battles, although the American surface fleet did achieve some operational success by preventing some bombardments of Guadalcanal. One bright spot for the Americans occurred on the night of 11-12 October off of Cape Esperance when Rear Admiral Norman Scott’s force of cruisers and destroyers, augmented by one battleship, lost only one destroyer while sinking one Japanese cruiser, damaging two more, and killing a Japanese admiral. Despite this tactical victory, the Americans were unable to gain control of the night. Two nights later, on the night of 13-14 October, two Japanese battleships sailed unopposed off of Henderson Field and conducted the most vicious shore bombardment the Marines on Guadalcanal were to experience. Japanese cruisers continued the bombardment over the next two nights. 28 One month later, on the night of 12-13 November, a powerful Japanese task force, hoping to repeat the bombardment, smashed an American force of cruisers and destroyers and killed both of its admirals. Tactical victory again went to the Japanese in this action, although the Americans did accomplish their operational goal of preventing the planned Japanese bombardment of the island in this later engagement. The Americans also turned a tactical defeat into an operational victory the following night, 13-14 November, when Rear Admiral Lee’s Task Force 64 sank one Japanese battleship and forced the rest of the force to withdraw, at a cost of one battleship and four destroyers sunk or heavily damaged. Although the entirety of this action is widely considered an American victory, American pilots from the carrier Enterprise earned much of the credit by sinking or damaging one battleship, four cruisers, and seven troop transports the following day. 29

Figure 5: A victim of insufficient pre-war preparation, USS Quincy (CA-39), photographed from a Japanese cruiser during the Battle of Savo Island, off Guadalcanal, 9 August 1942. Quincy, seen here burning and illuminated by Japanese searchlights, was sunk in this action. (Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 50346)

Mahnken claims that at one point the Americans did, in fact, change their tactics and that Rear Admiral Scott won this tactical victory because he “had studied previous engagements…and had carefully trained his force in night-fighting tactics.” 30 Furthermore, the characterization of the American surface fleet’s defeats over the course of the Guadalcanal campaign does not tell the whole story, since, in fact, the U.S. Navy ended up exchanging roughly equal warship damage over the course of the campaign and saved the Marines ashore on 13-15 November. Nevertheless, while the American surface fleet at Guadalcanal did claim a few tactical victories, such as the Battle of Cape Esperance and the night of November 13 that killed Rear Admirals Scott and Callaghan, usually the victory came about as a more intact Japanese force withdrew after taking less losses than the Americans. When meeting Japanese forces at night, the U.S. Navy’s failure to adjust its tactics kept leading to defeat as capped by the night action off of Tassafaronga on November 30. Here, despite enjoying a near-perfect radar picture and situational awareness, the American fleet lost one cruiser sunk and three damaged to an outnumbered force of Japanese destroyers at night. 31

Lessons for Today

While today’s commanders may not be able to predict exactly how their future enemy may fight, they will be expected to learn from mistakes and quickly adapt in order to become, in Admiral Locklear’s words, lethal and dominant. Although the Americans’ poor prewar assumptions about the nature of the coming conflict likely preordained the first defeats in night combat, an inexcusable failure to identify and address the root causes led to further unnecessary losses. Unlike the submarine force in the Pacific War, the admirals in charge of the surface fleet at Guadalcanal made little effort to change anything about how they were fighting over the months of the campaign. Mahnken attributes much of the credit for Japan’s success to continuity of command, by which it was able to “use combat experience to modify and improve upon its prewar doctrine,” and similarly finds its lack on the American side as the prime reason for successive defeats. 32 This explanation, however, misses the greater problem for the Americans, that they had foregone adequate prewar preparations and, after successive defeats, failed to find and correct the root causes of their failure.

Conclusion

Admiral Locklear sets a high bar for his commanders today by expecting them to arrive to his theater and become lethal and dominant. Had he been Pacific Fleet commander at the start of World War II, he would have been sorely disappointed by the inability of his submarine or surface fleets to fulfill this expectation. However, his commanders today can learn from the lessons of these two campaigns by making a realistic appraisal of their likely enemy and developing and exercising their own doctrine to counter his tactics. Most importantly, should a conflict occur, they should actively look for signs of failure, even expect these prewar tactics to fail, and then quickly identify the root causes and make corrections.

(Return to the July 2014 Issue Table of Contents)

- Thomas Mahnken. “Asymmetric Warfare at Sea: The Naval Battles off Guadalcanal, 1942-1943.” Naval War College Review, vol. 64, no. 12 (Winter 2011), page 98. ↩

- Ibid., 99. ↩

- Ibid., 100. ↩

- Samuel Locklear. “Speech at the Surface Navy Association Conference.” 26th National Symposium. Surface Navy Assocation. Arlington, Virginia. 15 Jan 2014. Speech. ↩

- Holwitt, 29-30. ↩

- Ibid., 86. ↩

- Samuel Flagg Bemis, “Submarine Warfare in the Strategy of American Defense and Diplomacy, as quoted in Holwitt, 87. ↩

- Joel Ira Holwitt. “Execute Against Japan”: The U.S. Decision to Conduct Unrestricted Submarine Warfare. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2009, page 87. ↩

- Ibid., 77. ↩

- Ibid., 75. ↩

- Ibid., 76. ↩

- Stephen Peter Rosen. Winning the Next War: Innovation and the Modern Military. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991, page 136. ↩

- Ibid., 136. ↩

- Ibid., 137. ↩

- Ibid., 139. ↩

- Ibid., 139. ↩

- Eric Larrabee. Commander in Chief: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, His Lieutenants, and Their War. First Naval Institute Press paperback edition. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2004, page 397. ↩

- Rosen, 139. ↩

- Carl Von Clausewitz. On War. Edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989, page 139. ↩

- Baer, 136. ↩

- Mahnken, 99. ↩

- David C. Evans, and Mark R. Peattie. Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy 1887-1941. First Naval Institute Press paperback edition. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2012, page 275. ↩

- Mahnken, 101-102. ↩

- Trent Hone. “‘Give Them Hell!’: The US Navy’s Night Combat Doctrine and the Campaign for Guadalcanal.” War in History, vol. 13, no. 2 (2006), page 172. ↩

- Ibid., 174. ↩

- Ibid., 191. ↩

- Ibid., 177. ↩

- Mahnken, 103. ↩

- Larrabee, 300. ↩

- Mahnken, 108. ↩

- James Hornfischer. Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal. Bantam Books, 2011,pages 391-392. ↩

- Mahnken, 106. ↩