Robert C. McCabe

Maynooth University

Introduction

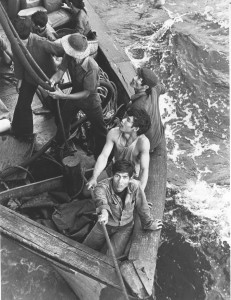

Vietnamese refugees come alongside USS White Plains (AFS-4) in 1979. Naval History and Heritage Command, Photo Archives L35-04.

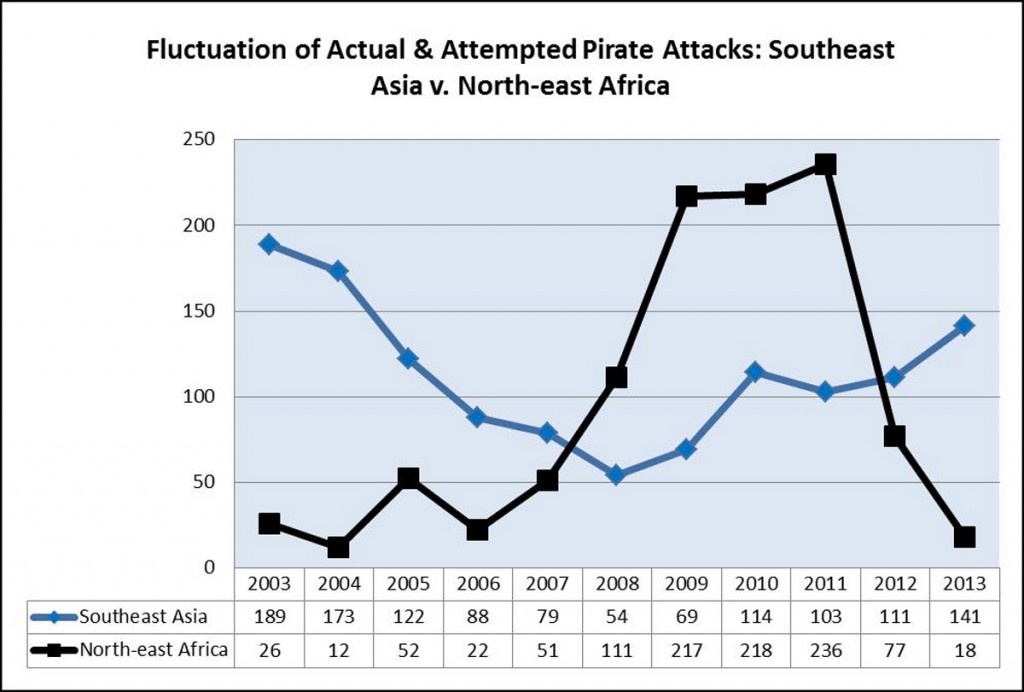

Between 2009 and 2012, the International Maritime Bureau (IMB), a specialised division of the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), recorded 648 reports of actual and attempted pirate attacks off the coast of Somalia and in the Gulf of Aden. In 2009, attacks in this region accounted for over 80 percent of all reported incidents worldwide. 1 The frequency and scale of these attacks were the highest since the IMB began gathering statistics on maritime piracy in 1992. This escalation in incidents and the development of a formalised hostage for ransom situation off the Somali coast placed the issue of piracy firmly in the media and public spotlight. However, despite the widespread attention these recent incidents generated, it was the waterways of Southeast Asia and not Somalia that played host to the first significant upsurge of contemporary maritime piracy. While piratical attacks against merchant vessels escalated as a by-product of the financial crisis that gripped the region in the late 1990s, the genesis of modern Southeast Asian piracy transpired much earlier. This manifested in a series of violent and concentrated attacks against Vietnamese boat refugees in the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea in the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s.

This article will firstly explore some of the reasons for this resurgence of piratical activity in Southeast Asia while illustrating some of the inherent difficulties that counter-piracy operations presented in the region and how they were addressed. This will be followed by an analysis of the efforts, both regional and international, initiated to counter this activity; focusing on the case of the Vietnamese boat refuges as a key example while also briefly referencing alternative episodes and responses. The small regional navies of Southeast Asia, in particular the Royal Thai Navy, were ill equipped to manage the piratical upsurge. The escalation of attacks in the late 1970s and 1980s would provide valuable operational lessons. Firstly, that interregional and international cooperation was vital in the suppression of maritime piracy and secondly, that maritime security issues could be just as destabilising as land-based threats and therefore merited investment and attention.

Problems with the statistics

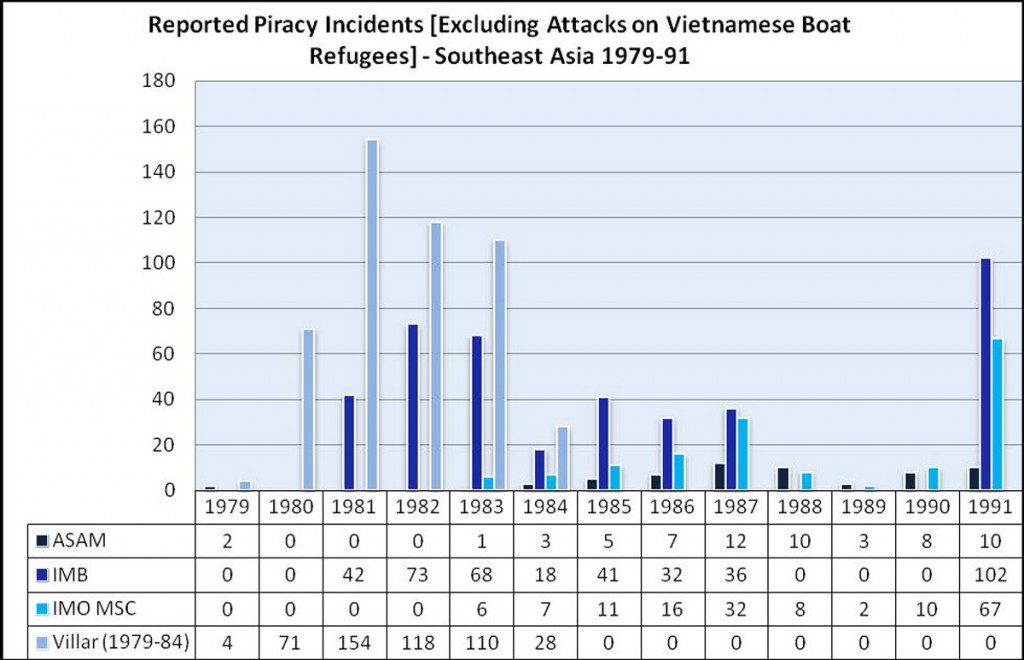

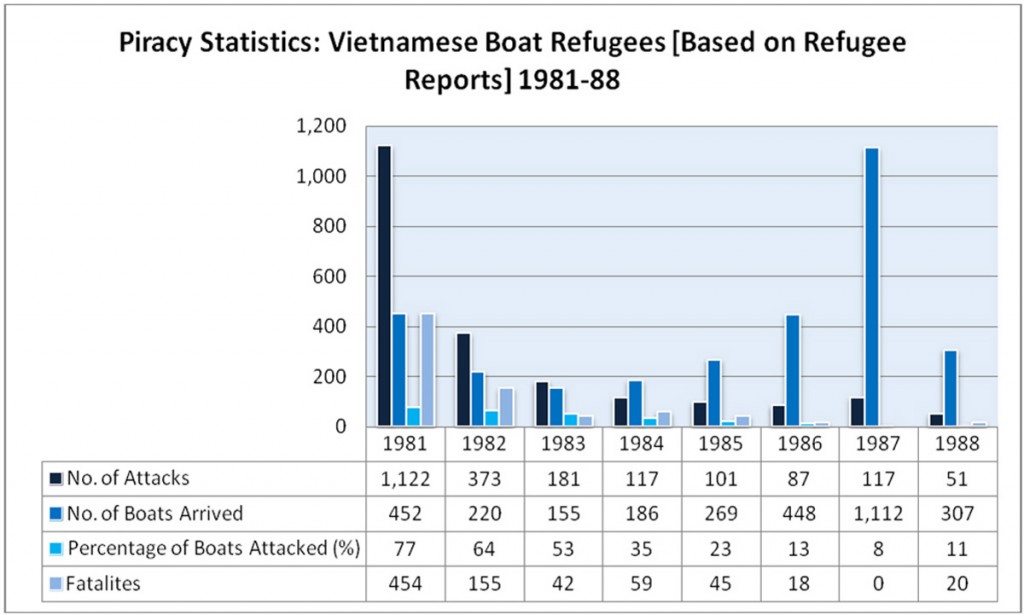

There exist only a limited number of reliable statistical sources to confidently gauge the level of piratical activity in Southeast Asia during the late 1970s and 1980s [see fig. I]. This changed somewhat following the establishment of the IMB Piracy Reporting Centre in Kula Lumpur in 1992. Prior to this the primary statistical sources consist of (a) the ‘IMB chronology of pirate attacks on merchant vessels 1981-87’ located in IMB founder Eric Ellen’s 1989 editorial Piracy at Sea (b) the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) Maritime Security Centre’s statistical resources from 1982-92 (c) Captain Roger Villar’s log of attacks from 1979-84 in his 1988 publication Piracy Today (d) the US National Geo-Spatial Intelligence Agencies’ Anti-Shipping Activity Messages (ASAM) and finally, United Nations’ Security Council reports. Supplementary to these are numerous eyewitness statements, victim correspondence, academic works, press releases and official governmental and law-enforcement publications. Despite this, it is widely acknowledged that the actual rate of incidents was significantly higher than what was reported or recorded.

There were a number of reasons for this under-reporting including the potential loss of international reputation, fear of reprisal, costly investigations and impediments, cultural acceptability and governmental complicity. Villar recognised this deficiency in his own record of piratical attacks: ‘It is the authors opinion that this is the most complete and comprehensive record in existence’. 2 He acknowledged however that ‘…it probably represents no more than about half the actual numbers of attacks which have taken place’. 3 This notion is reflected elsewhere. In 1998 the UK Defence Intelligence Service estimated that the annual number of actual piracy cases could be 2,000 percent higher than what was being reported whereas the Australian Intelligence Organisation estimated the rate of under-reporting by 1996 was somewhere in the region of 20 to 70 percent. 4 The inconsistencies with these figures reflect the difficulties in establishing accuracy when utilising modern piracy reports and data. Gauging the genuine effectiveness of counter-piracy initiatives before 1992 is therefore problematic. The available resources do however, allow for a reasonable assessment of the fluctuation of incidents.

Aside from these primary sources of information, there are also a number of secondary works that include analysis on Vietnamese boat refugees and additional regional piracies before the Asian financial crisis. However, these are frequently examined within in the wider framework of a broad discourse on contemporary piracy or with a particular interest group/ political agenda in mind, therefore often lack specific detail and focus on counter-piracy issues during this period. 5

Fig. I

Source: See: ‘IMB Chronology of Pirate Attacks 1981-87’ in Eric Ellen, Piracy at Sea (London, 1989), pp 241-71. ICC IMB, Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships: Annual Report 1992-2002 (London). IMO-MSC, ‘Statistical Resources on Piracy and Armed Robbery 1982-1992’. Roger Villar, Piracy Today: Robbery and Violence at Sea since 1980 (London, 1985), pp 92-153. US National Geo-Spatial Intelligence Agency, ‘Anti-Shipping Activity Messages 1979-1991’.

Context

Piracy as it had been traditionally experienced had declined drastically by 1900 aside from sporadic occurrences of opportunistic piracies, chiefly in the South China Sea, in the decades after the Second World War. This relative tranquillity was not to last, as a new and more violent wave of piratical aggression beset the waters of Southeast Asia in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Piracy is not a mono-causal issue. Several diverse factors can be attributed to its resurgence; chiefly colonial regression, post-conflict inheritance, the growth of global seaborne trade, economic hardship and inefficient coastal security facilitated by favourable geography. The cultural and political history of the region also undoubtedly contributed to the rise of piracy given the entrenched acceptance of many indigenous communities on maritime raiding as a legitimate vocation. During the nineteenth century, this extended beyond simple criminality to the consolidation of regional economic and political power bases. Pirates could not function successfully without the support of these local networks for resources, shelter and the concealment and movement of illicit goods. Indeed, piracy had never been totally eradicated from the region only suppressed to manageable levels. In the southern Philippines and northern Borneo, for example, piratical attacks continued throughout the 1950s and 1960s only on a ‘smaller – but still frequent – scale’. 6

Despite the inherent proclivity toward piracy that many of these coastal regions displayed, there was a distinct difference between the politically motivated piracies of the nineteenth century and the ‘systematic interdependent and interconnected…grey area activities’ 7 of pirates operating in the late twentieth century. Indeed, the European understanding of what constituted ‘piracy’ was quite at odds from that of the local inhabitants of maritime Southeast Asia for whom maritime raiding was often considered a ‘legitimate political or commercial endeavour’. 8 Therefore, ‘piracy’ from a western understanding only began to materialise in Southeast Asia in direct correlation with the expansion of European colonial enterprise there. James Warren’s study into the globalisation of maritime raiding and piracy in the region extrapolates this issue in more detail; he states: ‘the term [piracy] subsequently criminalised political or commercial activities in Southeast Asia that indigenous maritime populations had hitherto considered part of their statecraft, cultural-ecological adaption and social organisation’. 9

With this in mind, one of the underlying reasons as to why elements of these maritime communities began pirating in an extensive manner in the late 1970s was a substantial increase in poverty and economic hardship due to the commercial exploitation of fish stocks in the region. The availability of new technology developed since the 1950s enabled larger fisheries to procure catches at accelerated rates. Combined marine catches from Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam increased fourfold between 1960 and 1980 from 1.5 million tonnes per year to 5.5 million tonnes per year. 10 This growth was stimulated by destructive mass-fishing techniques such as trawling, fish-bombing and cyanide poisoning. 11 This large-scale illegal fishing led to a significant depletion in fish stocks, which directly affected the smaller coastal communities for whom fishing was the single leading source of revenue. The experience was more acute in parts of Indonesia, which was described as ‘the poorest of the poor’. 12 Carolin Liss affirmed the effect: ‘Over-fishing, pollution and the ensuing poverty of fishers and their families’ impacts directly upon the occurrence of piracy in Southeast Asia’. 13 A number of these fishermen turned to pirating vessels to supplement their loss of income. Indeed it was aggrieved fishermen turned pirates who were initially responsible for some of the most ferocious piracies seen in modern times; that of the attacks on Vietnamese boat refugees. These attacks were largely responsible for amplifying piracy reports in Southeast Asia in the early 1980s due to the brutality and frequency of the incidents, which placed the issue on a wider international stage.

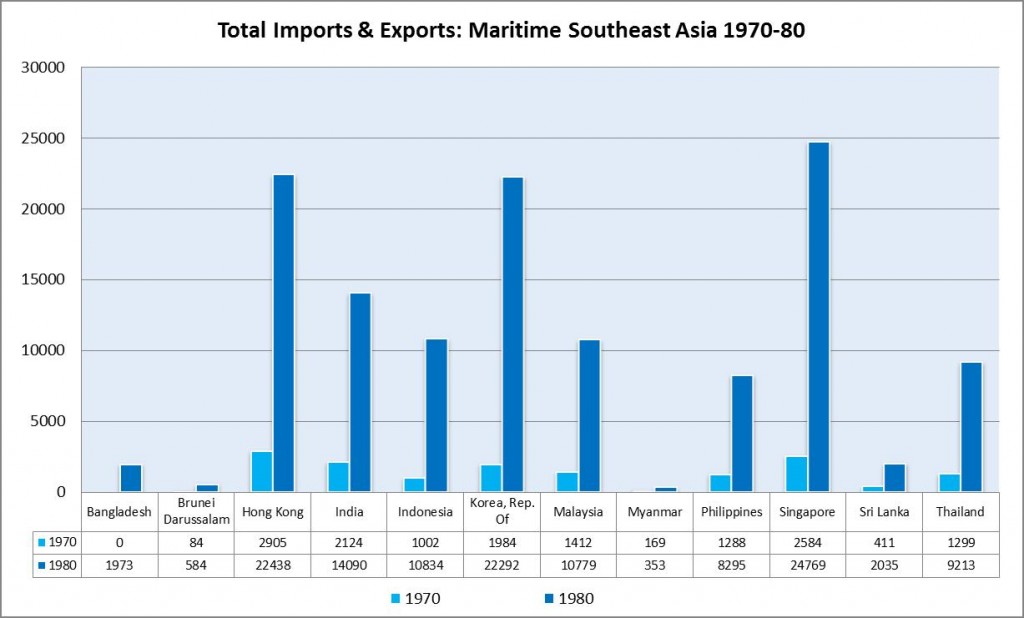

Over-fishing and increased pollution were by-products of the spread of the global market-driven system and globo-economic interdependency. This led to an exponential growth in maritime trade transiting Southeast Asia throughout the 1970s and 1980s [see fig. II]. Indeed, the last four decades have witnessed a quadrupling of total seaborne trade, from just over 8 thousand billion tonne-miles in 1968 to over 32 thousand billion tonne-miles in 2008. 14 This rapid economic development did little to benefit the poorer coastal regions. Instead, it widened the gap between rich and poor and further isolated already disparate communities. According to Graham Ong Webb economic globalisation had the effect of ‘reinforcing the conditions that compel marginalised maritime-orientated communities to turn to piracy’. 15

The Indonesian island of Batam serves as an example of the destructive and dissociative elements of this economic activity at a local level. Batam witnessed a huge growth in manufacturing industries during the 1980s that transformed it from a small fishing community to a major industrial hub. Eklöf described how an influx of migrants came to the island in search of employment but ‘were unable to find work in line with their expectations and education (or) find any work at all’. 16 The result was a rise in criminal activity such as piracy. The growth in maritime freight through the area also presented potential pirates with an abundance of high value targets transiting narrow and congested shipping-lanes. This new wave of piratical activity, facilitated by the rise of the consumerist system, was further enhanced by the decline of the colonial system. Historically in the ‘clash between the policies of free trade and the policies of territorial assertion, that is where the roots of piracy can be found’. 17

Fig. II

Source: Compiled from UN Department of economic and social development statistical office, 1992 International trade statistics yearbook, vol. 1 (New York, 1993), p. 1051.

Source: Compiled from UN Department of economic and social development statistical office, 1992 International trade statistics yearbook, vol. 1 (New York, 1993), p. 1051.

Southeast Asia was to experience an era of rapid colonial regression in the years and decades following the Second World War. The resultant governments that emerged were fragile, under-resourced and over-pressured and struggled therefore to establish effective regional security. This instability was particularly evident in some of the more isolated coastal communities. These problems reflected, according to Peter Earle: ‘…the maritime dangers of a post-imperial world in which the navies of the great powers can no longer patrol where and how they wish and former colonies have neither the naval power nor the resources and will to eradicate the problem’. 18 The former British colony of Singapore was, to some extent, the exception to this. In the years after independence from Britain (and later Malaysia), the newly formed government began actively seeking foreign direct investment which eventually transformed the small state from a colonial trading outpost to a robust export economy. For most regional states, investment went into developing the army in the years after decolonisation and not maritime security capabilities. In the Philippines for example, this was primarily due to internal threats from communist organisations such as the New People’s Army, the military wing of the communist party of the Philippines, and later from Islamist separatist groups such as the Moro National Liberation Front and Abu Sayyaf in the South.

During the colonial period, maritime Southeast Asia featured a major western naval presence, which kept piratical incidents and disorder at sea to a minimum. The decline of ‘Pax Britannica’ and colonial control meant that this stabilising naval presence regressed. The progressive process of decolonisation essentially concluded when Britain announced its withdrawal from Singapore and Malaysia in January 1968, which was not completed until 1971 as a diplomatic concession to the Singaporean government. This was part of Britain’s wider strategic withdrawal ‘East of the Suez’ 19 owing to the heavy economic and financial burden of maintaining foreign naval bases. Parliamentary papers at the time estimate the naval base in Singapore consumed 15% of the British defence budget and 40% of defence costs overseas. 20 The haste in which Britain abandoned its naval presence left the waterways of the region unpatrolled and vulnerable. This weak new maritime security environment was acutely felt in the ex-colony and further afield. The Former Prime Minister of Singapore Lee Kuan Yew commented: ‘I was completely incredulous that there could be such a rapid chop and change…All I am asking you is to show the flag so that no rapacious attack will take place’. 21 The earlier American withdrawal from the Philippines in 1949 had provoked similar concerns and illustrated the vulnerability of the maritime environment without a commanding naval presence. The British legation in Manila wrote to the minister of state for foreign affairs describing the challenges facing the authorities following the withdrawal:

But now the American officers are gone and the Philippine authorities have not hitherto shown themselves capable of maintaining the constabulary at its old standards…The result among the Moros is, I fear, that they are reverting to type and are again finding in piracy and smuggling an easy way of making a living. 22

Combined with endemic poverty, weak governance and an increase in regional commercial activity, the maritime climate was heavily conducive towards illicit criminal activity such as piracy. The fledging national legal framework that developed after colonial regression was predominantly based on that of the former colonial powers with an emphasis on consolidating the rule of law. However, given what Graham Ong-Webb refers to as the ‘trappings’ of the globalised system – economic growth, the rise of ports and commercial maritime traffic 23 – these under resourced states were unable to rival the naval presence that their former imperial rulers offered. This lax coastal security was exacerbated by little or no multilateral cooperation in attempting to counter regional piracy in the early years of the re-genesis.

The conditions outlined above were further amplified by the availability of weaponry inherited from several regional conflicts during the post-war years. The saturation of many parts of Southeast Asia with military grade weaponry enhanced the capabilities of pirates and undoubtedly encouraged the spread of the activity. More worryingly for authorities the availability of this weaponry increased the levels of violence witnessed during piratical attacks in Southeast Asian waters particularly in the Gulf of Thailand and the Philippines throughout the 1980s. The issues described above combined to create the conditions for a resurgence of maritime piracy in Southeast Asia.

The initial victims of this new wave of piracy were the hapless ‘boat people’ fleeing Vietnam in a mass maritime exodus across the Gulf of Thailand 24 and the South China Sea. Indeed, it was this huge migration of people and valuables that presented disparate elements of impoverished coastal communities with an opportunity to recoup some of their material and financial losses. What began as opportunistic robberies on vulnerable targets by indigent local fishermen soon escalated into unprecedented violence and brutality that involved organised criminal elements. Piracy was not just confined to the Gulf of Thailand or the South China Sea however, as other regions of maritime Southeast Asia also witnessed a rise in maritime predations during this period. By 1991, according to one analyst, ‘these assaults have been of sufficient quantity to consistently designate Southeast Asia as, by far, the most piracy-prone region of the world’. 25

General obstacles to regional counter-piracy operations

Prior to analysing any specific counter-piracy measures initiated by regional and international actors in response to the re-genesis of piracy in the late 1970s, it is important to examine some of the enduring difficulties that maritime security operations have faced in the waters of Southeast Asia. Just as it facilitated piracy in previous centuries, the distinctive geographic features of the region hampered counter-piracy operations throughout the 1980s and 1990s. The Malay Archipelago, also known as the East Indies, which incorporates Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines is the largest in terms of surface area on earth, consisting of over 25,000 islands, many of which are uninhabited. Indonesia alone is comprised of 13,667 of these islands resulting in approximately 93,000 square kilometres of inland seas. 26 Topographically the Philippines possess one of the longest coastlines of any nation on earth due to its archipelagic configuration. Thailand also possesses a significant coast line of 2,420 kilometres on the Gulf of Thailand and the Andaman Sea whereas Singapore, despite a coastline of just 138 kilometres, was in terms of shipping tonnage, the world’s busiest port in 1988. 12 What this meant in terms of sea based counter-piracy action was that it made engaging pirates in any extensive way almost impossible. They could evade capture by crossing into other maritime jurisdictions or sheltering among the many bays, estuaries, rivers, reefs and tree-lined inlets beyond the reach of their pursuers.

Merchant vessels that approached the region from the west were funnelled into the narrow geographical chokepoint of the Malacca Strait, just 1.7 nautical miles at its narrowest point, as the most direct route to ports in north-east Asia. Similarly, the Singapore Strait and the Strait of Malacca constituted the main Sea Line of Communication (SLOC) between the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean. In 1982 an estimated 43,633 vessels transited the Malacca Strait. By 1993 this figure had risen to 91,826 vessels, an increase of 128.9% in a little over a decade. 28 These congested shipping lanes presented pirates with an abundance of slow moving ‘easy’ targets proximal to safe havens and sanctuaries ashore. The sheer scale of the maritime environment and coastline meant that any patrols initiated by the small regional navies were largely ineffective. Simply put, the geographic character of the region bolstered and encouraged illicit maritime activity while simultaneously hampered the ability to counter it. This was also the case during the nineteenth century. As Warren accurately observed: ‘They simply had to wait, sheltered behind a convenient island, headland or bay overlooking strategic sea-routes, and sooner or later ‘coastwise’ targets, never straying out of sight of land, would cross their path’. 29

Given this complex geographic setting it is little surprise that maritime territorial disputes arose. These disputes evolved primarily in reaction to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1982, which solidified the legal limits of a nation’s territorial sea (12 nautical miles from shore baseline), contiguous zone (24 nautical miles from baseline) and Exclusive Economic Zone or EEZ (200 nautical miles from baseline). In the congested and archipelagic waters of Southeast Asia these boundaries often overlapped resulting in a lack of clear jurisdiction, bitter legal disputes and, as a result, a breakdown in regional maritime relations. The territorial dispute that emerged over ownership of the resource rich Spratly Islands in the South China Sea for example illustrated the problem in this regard. Following the introduction of the EEZ under articles 55, 56 and 57 of UNCLOS, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Brunei claimed exclusive territorial rights to all or part of the islands. These opposing claims led to a number of political and military engagements during the 1980s and 1990s weakening regional relations and creating instability in the maritime environment. Pirates operating in the region manipulated this instability to their advantage.

Peter Chalk highlights an incident from May 1992, which illustrates how this negatively affected unilateral counter-piracy operations. He described how a stolen trawler operated by pirates was stalking vessels near the disputed region of Sabah off the northeast coast of Borneo. The trawler was spotted by a Royal Malaysian Police marine patrol that commenced pursuit. The Malaysian vessel was forced to call off its pursuit when the trawler entered into Philippine territorial water as ‘no agreement of posse comitatus had been reached between Manila and Kuala Lumpur’. 30 Given this complex maritime environment, multilateralism and continuity, vital for effective counter-piracy operations, was not forthcoming.

These issues were compounded by allegations of corruption and governmental complicity. Empirical data, chiefly eyewitness testimony reported by shipmasters, suggests that this was an issue in China, Indonesia and the Philippines at various times throughout the period. Some argue that this manifested itself in ‘official sanctioning and collaboration’ 31 while others suggest, in the case of Indonesia for example; ‘[that pirates were] either actual members of the…armed forces or at least benefit[ted] from close links with Indonesian military and customs units…’ 32 . Jon Vagg suggests ‘…it is possible that [armed forces] condoned, assisted and ‘taxed’ non-military pirates just as they would many other illegal enterprises’. 33 This complicity was also evident in relation to attacks on boat refugees in the Gulf of Thailand. Numerous allegations of incompetence, abetment and collusion with pirates were directed at the Thai government in the 1980s. Pascal Dupont who reported for the French news weeklies Actuel and L’Express during the 1980s, alleged that in the spring of 1981, nineteen Vietnamese refugees were executed by the Thai Navy after they had killed several Thai pirates that had attacked them. 34 Duong Phuc and Vu Thanh Thuy, a Vietnamese couple who were victims of a pirate attack, suggested that the Thai government simply ignored the crisis in an attempt to discourage ‘new waves’ of refugees from seeking temporary refuge in Thailand. 35 The Vietnamese/American Boat People SOS committee, founded in 1980, made their dissatisfaction with Thai anti-piracy efforts clear in a white paper published in 1981:

Thai pirates, operating with virtual impunity in the Gulf of Siam, are subjecting thousands of refugees to ordeals of rape, robbery and murder. The unarmed refugees in their rickety fishing boats can neither escape nor defend themselves against the heavily armed pirates. The sickening tales told by survivors of these attacks should long ago have moved Thai officials to act. Instead, the Thais say only that they lack the resources to police a 2,000 mile coastline. While that is undoubtedly true, it is also apparent that Thai police and naval units are not even trying…It has been suggested that Bangkok’s willingness to look the other way as Thai pirates plunder, rape, and kill is the government’s way of discouraging new waves of refugees from seeking temporary haven in Thailand. If so, it is a vile tactic fully deserving of international condemnation. 36

Thai officials vehemently denied such allegations. The then Thai Secretary General, Chamlong Srimuang, responded to similar claims in April 1980:

The pirate activities in the Gulf of Thailand do not take place in the Thai territorial waters only…Our Police Marine has to combat against those terrorists who, from time to time, attacked not only the Vietnamese boat people but also those of Thai nationality as well…Furthermore the long eastern coast of Thailand does not facilitate our small marine force to accomplish such operation. 37

Regardless of whether the Thai government acted improperly or not, this response is reflective of the inherent difficulties small regional navies encountered in attempting to combat piracy in Southeast Asian waters.

The situation was further exacerbated by the inadequacies of the coastal states’ naval resources in the late 1970s and 1980s. As previously mentioned, state investment in the years following decolonisation focussed on strengthening land forces at the neglect of maritime security capabilities. Eventually attempts were made to modernise naval assets, however, this initially focussed on securing large patrol craft such as frigates, antisubmarine warfare corvettes, and missile-equipped surface combatants. Thailand, for example, entered into an agreement with China in 1988 and 1989 to acquire 4 Jianghu class and 2 Naresuan class frigates. 38 By 1997, Thailand had acquired a small aircraft carrier from Spain, a decision that reportedly perplexed its neighbours. 12 These uneconomical investments did little to benefit maritime security operations or promote regional cooperation. Instead, they illustrated that national prestige was favoured over utility – an indication of the insular nature of regional states at the time. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) was established in 1964 to facilitate regional cooperation and encourage multilateral engagement. However, ASEAN was primarily concerned with the idea of nation building and economic consolidation and as such did not result in enhanced cooperation at sea. Keeping these causative factors in mind, a more revealing examination of regional and international efforts to counter the pervasive piracies against Vietnamese refugees in the Gulf of Thailand will be undertaken.

Vietnamese boat refugees 1979-91

Reports of pirate attacks on refugee boats transiting the Gulf of Thailand began to surface following communist victories in Vietnam in 1975, which resulted in large numbers of people fleeing the country, many of them by boat. However, the outbreak of hostilities between the People’s Republic of China and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam in early 1979 intensified this exodus drastically resulting in an estimated 2,000 refugees arriving in Thailand each month of 1979 40 . This figure had risen to 6,000 per month in 1980. 12 In 1981 a total of 15,479 refugees in 452 boats arrived in Thailand. 42 It is estimated that a staggering 77% of these boats were attacked by pirates operating in the Gulf of Thailand – an average of 3.2 times per attacked boat. 43 This amounted to a massive 1,112 attacks in 1981 alone. Despite the high frequency of incidents, it was the manner in which they were carried out that brought the issue to the attention of the international community. Reports for 1981 suggest that 571 female refugees were raped, 228 refugees were abducted and 454 refugees were murdered by pirates. TIME magazine described these events as a ‘Liquid Auschwitz’ in an article written in July 1979, the same month that the UN summoned a conference at Geneva to discuss the Indochinese refugee crisis. The typical modus-operandi of an attack is reported below:

Vietnamese boat left Vung Tau on 29 July [1983] with 28 people. Seven or eight pirates rammed it shortly after with a radar equipped fishing boat and threw most of the Vietnamese into the sea where they were left to drown. Gold and valuables stolen. Women raped repeatedly. Only two known survivors 44

The unprecedented levels of violence and brutality resulted in widespread condemnation and international pressure on the Royal Thai Government (RTG) to suppress the pirates operating in their territorial waters.

Fig. III

Source: ‘Piracy Statistics (Based on Refugee Reports)’ in Eric Ellen, Piracy at Sea (London, 1989), p. 282.

Source: ‘Piracy Statistics (Based on Refugee Reports)’ in Eric Ellen, Piracy at Sea (London, 1989), p. 282.

As early as June 1980 the RTG publicly stated its intention to mount a more ‘active’ campaign against the pirates and requested international assistance in the endeavour. 45 The under-resourced and overstretched character of Thailand’s maritime capability meant it could not tackle the problem in isolation. In 1980, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), in what appeared to be a reactive gesture, provided the Thai Navy with a high speed, unarmed surveillance vessel to support anti-piracy patrols. However, the first tangible anti-piracy programme was not initiated until February 1981. This brief scheme was a bi-lateral endeavour between the United States and the RTG facilitated by a $2 million US donation to subsidise operational expenses. The initiative lasted just seven months; dissolving in September due in part to disputes over financial maintenance. It has been suggested difficulties arose as a result of investment in expensive and largely ineffectual air-sea surveillance, chiefly two twin engine O-2 spotter aircraft and a Thai coastguard cutter. 46 Despite this, the scheme had some limited success and paved the way for further cooperative initiatives. Twenty-five suspects were arrested and charged with piracy, five suspected pirate vessels were seized and an estimated 180 boat people were assisted while under attack. 47

Following a series of delays and negotiations, a more comprehensive and calculated counter-piracy initiative was launched on 23 June 1982. The Anti-Piracy Arrangement (APA) was convened under the auspices of the UNHCR and subsidised by donations from twelve countries: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Federal Republic of Germany, France, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland, United Kingdom and the United States. A total of $3,672,033 was donated; $1.2 million coming from the United States government. 48 The operation was headed by the Thai navy anti-piracy unit from the coordination centre in the southern province of Songkhla with a nine man team stationed on small offshore islands, such as the notorious Koh Kra. Koh Kra Island had become synonymous with the worst of the violence and depredation witnessed in the piracies. Numerous graphic victim testimonies exist which relay the inhuman conditions suffered by the refugees abducted and held there by pirates. One eyewitness described the ‘sad scene that all people brought to the island must suffer’. She stated: ‘The men were tortured and beaten to find out where valuables were hidden, the women were gang-raped by different bands of pirates, which at the high point came to 50 different fishing boats clustered around the entrance to the island’. 49

A number of landward and seaward counter-piracy initiatives were spearheaded under the APA. An anti-piracy surface unit was established that consisted of three sixteen-metre fast patrol craft, six special operation task trawlers alongside a number of rubber patrol boats. The surface unit was complemented by an aircraft unit consisting of five surveillance aircraft including spotter planes that coordinated with the surface unit and land base to identify vulnerable vessels and patterns of piratical activity. Patrols were executed on a twenty-four hour rotating basis. The funds donated to the APA were also used for the enhancement of post-incident investigations, the strengthening of land-based information gathering, upgrading of communications equipment and a harbour department registration and licensing programme. 50

Despite these improvements and investments, the extent of the APA’s operational zone was limited. The available resources meant that only allowed a small section of the Gulf of Thailand could be monitored and patrolled. Roger Villar remarked: ‘Even twice that force would have little chance of covering so large an area effectively’. 51 Despite these limitations, the APA did achieve some success. Incidents of piracy dropped from 373 in 1982 to 117 in 1984 a decrease of over 50%. 52 The number of reported deaths at the hands of pirates also declined from 176 in 1982 to 59 in 1984 (see fig. III). 12 While it is evident that the 1982 anti-piracy arrangement did contribute to a reduction in attacks, the reduction in the flow of refugees must also be recognised as a contributory factor. The total number of refugees recorded as arriving in Thailand in 1981 was 15,479. This had dropped to just 3,343 in 1983 indicating a substantial decrease in refugee movement. 52

The UNHCR/RTG counter-piracy programme was extended in 1984 and witnessed an important progression from sea-based operations to land-based initiatives, primarily on the recommendations of a US interagency task force. Lessons learned from earlier operations meant that emphasis was placed on training, intelligence gathering and judicial development over acquiring expensive naval and air assets. It was acknowledged that the root cause of piracy was ashore, a fundamental realisation in the evolution of regional counter-piracy efforts. A number of substantial initiatives were launched under the 1984-87 programme, principally in relation to the apprehension and prosecution of suspected pirates. At the lowest level, this took the form of educative crime prevention, considered vital given the chiefly opportunistic nature of the piracies. 55 At the highest level, this resulted in several prosecutions and convictions.

From January 1982 to December 1985, just 30 suspects were arrested for offences against boat people, 56 reflective of the emphasis placed on sea-based counter-piracy operations under the APA. Under the new programme, 66 suspects were arrested in a little under two years between January 1986 and October 1987. 12 The sentences handed down ranged from two to fifty-years imprisonment, with one pirate sentenced to death in December 1986. The harshness of the sentencing was undoubtedly designed to act as a deterrent to those considering committing piratical acts. These positive results were facilitated by the development of compulsory computerised registration and a paid ‘informer’ system under the guidance of US law enforcement personnel. The UNHCR Poul Hartling commented in an address to the general assembly in 1985:

…very encouraging has been the increasing efficiency with which the Thai authorities are implementing the Anti-Piracy Arrangement…the deterrent effect is definitely beginning to show up in the statistics…I believe this can be a source of satisfaction both for the Thai authorities and the donors who have steadfastly supported their efforts to combat this evil. 58

Aside from efforts at the political and military level, the UNHCR also initiated programmes designed to encourage masters of commercial vessels transiting international waters to assist refugees who may be vulnerable to attack or may have suffered an attack. This request was initially met with some trepidation principally due to potential financial ramifications. The first of these initiatives, the ‘Disembarkation Resettlement Offers’ (DISERO), was designed to encourage ships flying flags of states operating an open registry or ‘flags of convenience’ to aid in the rescue of refugees at sea by facilitating their disembarkation and resettlement in countries that contributed resettlement places. By 1985, eight countries offered resettlement places for refugees under the DISERO scheme. These were Australia, Canada, the Federal Republic of Germany, France, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States.

A second initiative was launched in May 1985 that offered to negate the financial burden of rescuing refugees at sea through ‘Rescue at Sea Resettlement Offers’ (RASRO). One month later in June 1985, a companion programme, the ‘Rescue at Sea Reimbursement Project’ allowed for costs directly related to the rescue of refugees to be directly reimbursed to ship-owners. The UNHCR circulated a pamphlet in 1985 that explained the procedures and guidelines for the disembarkation of refugees and reimbursement procedures. It stated: ‘On request, UNHCR will reimburse ship-owners for the subsistence of refugees on board ship…calculated at US$10 per refugee per day…The maximum amount reimbursed under any single claim should not normally exceed US$30,000.’ 59 These initiatives were bolstered by personal radio broadcasts from the high commissioner Poul Hartling encouraging and supporting shipmasters in the South China Sea to aid refugees in distress. These humanitarian and civilian initiatives had an immediate effect in disrupting piratical activity on the high seas. Hartling commented in 1985: ‘The appeals of UNHCR and the IMO have not fallen on deaf ears, and in the best traditions of the sea…ship-masters and crewmen – often at their cost, inconvenience, and sometimes personal risk – are going out of their way to save lives’. 60

The long-term impact of the rescue programmes should not be over-stated as the numbers rescued during the period 1985-87 were generally lower than the numbers from previous years. 61 However, the figures when expressed in relation to the total number of arrivals reveal a 5% increase in rescues between 1984 and 1985. 12 By 1987 only 8% of boats arriving in Thailand had reported being attacked compared to 23% in 1985, a partial indication of the achievement of the land-based counter-piracy initiatives. However, between 1988 and 1989 an upsurge in attacks resulted in an estimated 1,250 refugees killed by pirates and a sharp increase in abductions and incidents of rape. 63 The successful land-based initiatives, in particular the severe prison sentences, almost certainly had the effect of deterring the more opportunistic and presumably less violent ‘fishermen turned pirates’. This, according to W. Courtland Robinson: ‘[left] behind a hard core of professional criminals…[whom] were taking greater pains to leave no witnesses’. 64

Despite these setbacks the flow of refugees declined drastically by 1991. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War reduced the rigid economic limitations placed on Vietnam, which opened the door for small-scale private and foreign direct investment. This combined with the end of the repression of the Hoa people in the south resulted in substantial economic growth and stability in the country and as a consequence a sharp decline in the migration of refugees. This reduction predictably led to a decline in piratical attacks in the Gulf of Thailand. Elsewhere however, attacks in the region escalated. In December 1991 the UNHCR anti-piracy programme was terminated, not because the piracy problem had been eradicated, but according to final assessment report: ‘…it [had] reached the stage where it [could] be effectively managed by local agencies’. 65

The evolution in counter-piracy strategy and philosophy was apparent in the years following the decline in attacks on refugees. Most regional states recognised that at least partial cooperation and information sharing was necessary if effective counter-piracy measures were to be initiated. Southeast Asian states’ naval forces were still comparatively small in the early 1990s, especially when considered in relation to the vast sea space that would have to be monitored and patrolled. This meant that some form of strategic continuity was essential in any seaward anti-piracy operations.

Alternative initiatives 1991-97

Historically, multilateral cooperation in Southeast Asia had been complicated due to the geo-political character of the region and the challenges presented in implementing coordinated patrols in respective territorial seas. The existence of ASEAN framework, for example, did little to promote cooperation at sea. The issue of multilateralism was partly solved by the implementation of bilateral initiatives after 1991. It was far easier to coordinate patrols with the navy of one country rather than multiple countries. Japan attempted to bridge this gap in the 1990s by providing training and assistance to the littoral states. However, it was not until 2006 with the signing of the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia or ReCAAP, that multilateral cooperation on a governmental to governmental level was fostered and effectively utilised to combat regional piracy.

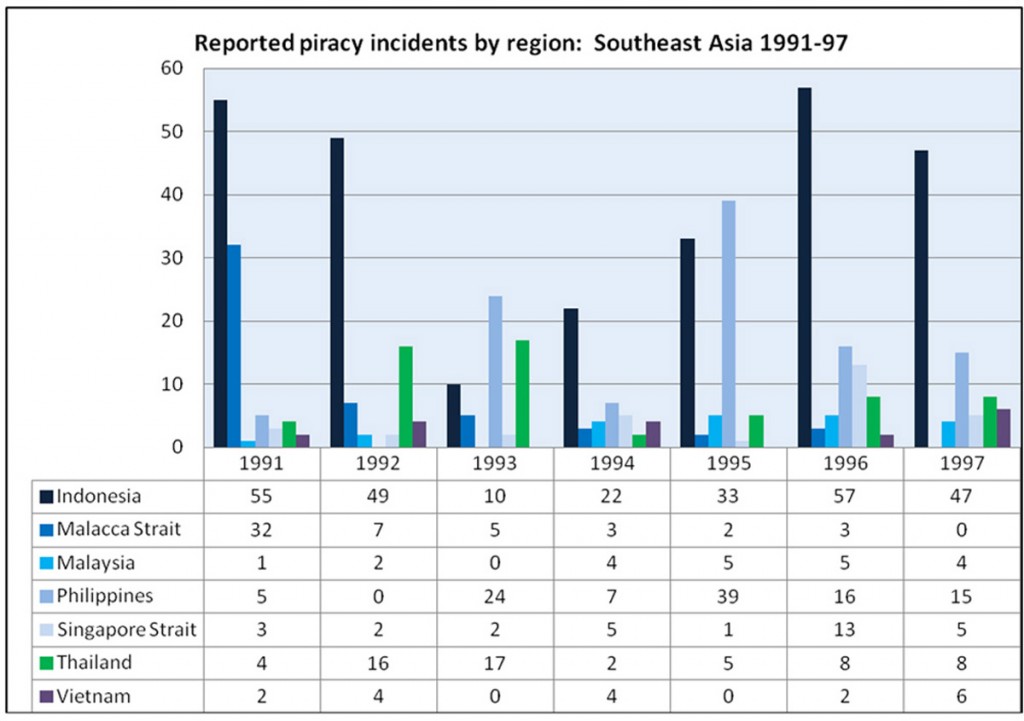

By 1991, regional piracy had escalated dramatically shifting predominantly from the Gulf of Thailand to the busy shipping lanes of the Malacca Strait and Indonesia (see fig. IV). There were 107 attacks reported worldwide in 1991. Notably, 88 of these occurred in Southeast Asian waters. 66 This equated to approximately 82% of all reported incidents worldwide. The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) responded by pressuring regional states to:

…increase their efforts as a matter of the highest priority to suppress and prevent acts of piracy and armed robbery against ships in or adjacent to their waters as well as to ensure that further and prompt action including strengthening of security measures is taken against pirates and armed robbers reportedly operating in their waters 67

Incidents such as the violent attack on the Valiant Carrier in April 1992, in which a pirate had stabbed an infant girl during a botched raid, placed further pressure on littoral states to initiate a resolute response to the problem. The IMO recognised the importance of a multilateral approach and invited neighbouring states to ‘co-ordinate their actions against pirates and armed robbers operating in areas within or adjacent to their waters’ 68 . Motivated partly by the mounting international pressure and the loss of reputation, there were a number of initiatives launched in 1992.

Fig: IV

Source: ICC IMB, Piracy and armed robbery against ships annual report: 2002 (London, 2003), p. 5.

Source: ICC IMB, Piracy and armed robbery against ships annual report: 2002 (London, 2003), p. 5.

Unilaterally Singapore, Indonesia and Malaysia began to increase the frequency of littoral patrols to interdict the movements of pirate groups along their respective coasts. These states also actively began to prosecute those suspected of engaging in piracy. Indonesia, for example, launched ‘Operation Eroding the Pirates’ (Operasi Kikis Bajak) in June 1992 which resulted in, according to the Far Eastern Economic Review, seventy arrests for piracy in a six month period between June and November 1992. 69 The Malaysian government created a special unit called the ‘Sabah Police Field Force Brigade’ (PFF) with the dual intention of curbing maritime piracy and the entry of illegal immigrants. The PFF deployed intelligence gathering techniques and placed brigade officers and staff in strategic locations along the Sabah coast to deter and interdict piratical activity in the Sulu Sea. 70 The brigade, which was based in Sandakan on the north-eastern coast of Borneo, had up to 40 patrol craft at its disposal. Aside from these unilateral actions, a number of bilateral initiatives were also instigated.

The neighbouring countries of Indonesia and Singapore signed a joint agreement in 1992 that provided for information sharing on regional piratical activities and coordinated anti-piracy patrols in the Singapore Strait and the Phillip Channel. These patrols occurred at a rate of four times per year, with one warship and one marine police vessel from Indonesia and Singapore for sixty days per coordinated patrol. 71 That same year Indonesia and Malaysia agreed to form a joint unit known as the Maritime Operation Planning Team to conduct coordinated patrols along their common borders in the Strait of Malacca. The mission consisted of four joint patrols annually involving customs, search and rescue and police. 72 Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore also concluded bilateral agreements between each pair of countries indicating their recognition that warships of either country may happen to enter territorial seas of other states in the course of controlling piratical activity. 73 Later, in 1994, Malaysia signed a ‘memorandum of understanding’ with The Philippines. This was the first of its kind and enabled both countries to conduct coordinated anti-piracy patrols along their common sea boundaries and to exchange information gathered from these patrols.

There were however, limits to these cooperation mechanisms. The then director of the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Coordination Centre was quoted as saying: ‘Under no circumstances would we intrude into each other’s territory…If we chase a ship and it runs to the other side, we let the authorities there handle it’. 74 This was reflective of the enduring difficulties confronting counter-piracy operations in the region.

The intensification of counter-piracy initiatives launched between 1991 and 1994 resulted in a short-lived reduction in incidents. The IMO recognised, in its 18th Assembly session in 1993: ‘…the significant reduction in the number of incidents of piracy and armed robbery against ships in the Malacca Strait area since the implementation of countermeasures by the littoral states, including co-ordinated sea patrols’. 75 In just twelve months reported attacks dropped to just 15 in Southeast Asian waters. This success was, however, short-lived. By 1994 reported incidents rose to 39 and peaked at a substantial 122 in 1996. 76 In 1997, the region was plunged into a financial crisis, which witnessed the emergence of a more sophisticated, more ruthless and more organised breed of pirate and the beginning of a new era of piracy in Southeast Asia.

Conclusion

Piracy resurged in Southeast Asia in the late twentieth century due to several diverse though not divergent factors, some of which have been discussed here. Indeed, when taken in its wider historical context, maritime piracy displays a cyclical pattern and as such has enjoyed frequent periods of substantial growth and decline even before the earliest days of transoceanic trading. It is evident that the issue tends to attract more attention in times of relative peace when navies and governments are not concerned with macro-maritime issues such as the defence of trade in wartime. The early part of the period discussed here witnessed violent piratical attacks on defenceless boat refugees alongside opportunistic hit and run robberies in the regions busy sea-lanes. As the 1990s progressed these groups grew more organised and began hijacking larger targets. Regional states also recognised the benefit of organisation and cooperation in counter-piracy endeavours and began to coordinate and focus their efforts in a more substantial way.

In 2012, the IMB recorded 104 actual and attempted pirate attacks in Southeast Asian waters, the highest since 2004. In the same year, just 62 incidents were reported in the Gulf of Aden and Somali Basin indicating a considerable shift in piratical incidents back toward Southeast Asia (see fig. V). Given that that there are no failed states in Southeast Asia as opposed to Somalia, counter-piracy strategies must be formulated from a regional perspective with both historical and modern intricacies in mind. It is important therefore, that knowledge of the successes and failures of previous counter-piracy operations are analysed to facilitate more effective counter-piracy initiatives in the immediate present and foreseeable future.

Fig. V

Source: ICC IMB, Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships: Annual Report 2005 & 2012.

Source: ICC IMB, Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships: Annual Report 2005 & 2012.

(Return to the January 2015 Issue Table of Contents)

—————————————————

- ICC International Maritime Bureau, Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships: Annual Report, 1 Jan. – 31 Dec. 2009 (London, 2010), pp 5-6. ↩

- Roger Villar, Piracy Today: Robbery and Violence at Sea since 1980 (London, 1985). p. 92. ↩

- Villar, Piracy Today, p. 92. ↩

- See: US Office of Naval Intelligence & US Coast Guard Intelligence Coordination Centre, ‘Threats and Challenges to Maritime Security 2020’ (Mar. 1999) available at: Federation of American Scientists, (http://www.fas.org/irp/threat/maritime2020/TITLE.htm) (8 Oct. 2012). ↩

- See for example: Peter Chalk, Contemporary Maritime Piracy in Southeast Asia (1998), Stefan Eklöf, Pirates in Paradise: A Modern History of Southeast Asia’s Maritime Marauders (2009), Jack A. Gottschalk et al., Jolly Roger with an Uzi: The Rise and Threat of Modern Piracy (2000), Derek Johnson and Mark Valencia, Piracy in Southeast Asia: Status, Issues and Responses (2005), Peter Lehr (ed.), Violence at Sea: Piracy in the Age of Global Terrorism (2007), Carolin Liss, Oceans of Crime: Maritime Piracy and Transnational Security in Southeast Asia and Bangladesh (2011), Martin N. Murphy, Small Boats, Weak States, Dirty Money: Piracy and Maritime Terrorism in the Modern World (2009). Ger Teitler, Piracy in Southeast Asia: A Historical Comparison (2002), Roger Villar, Piracy Today: Robbery and Violence at Sea since 1980 (1988). ↩

- Stefan Eklöf, ‘The Return of Piracy: Decolonization and International Relations in a Maritime Border Region (the Sulu Sea) 1959–63’ in Working Papers in Contemporary Asian Studies, no. 15 (2005), p. 7. ↩

- Carolin Liss, Oceans of Crime: Maritime Piracy and Transnational Security in Southeast Asia and Bangladesh (Singapore, 2011), p. 6. ↩

- Carl A. Trocki, ‘Piracy in the Malay World’ in Ainslie T. Embree (ed.), Encyclopedia of Asian History, vol. 3 (New York, 1988), p. 262. ↩

- James F. Warren, ‘A Tale of Two Centuries: The Globalisation of Maritime Raiding and Piracy in Southeast Asia at the End of the Eighteenth and Twentieth centuries’ in Asian Research Institute: Working Paper Series, no. 2 (June, 2003), p. 3. ↩

- Daniel Pauly and Chua Thia-Eng, ‘The Overfishing of Marine Resources: Socio-Economic Background in Southeast Asia’ in AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment, vol. 17, no. 3 (1988), p. 202. ↩

- Warren, ‘A Tale of Two Centuries’, p.15. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Carolin Liss, The Roots of Piracy in Southeast Asia (Oct. 2010) available at: Nautilus Institute for Security and Sustainability (http://www.nautilus.org/publications/essays/apsnet/policy-forum/2007/the-roots-of-piracy-in-southeast-asia) (19 Apr. 2011). ↩

- Maritime International Secretariat Services, ‘Shipping and World Trade: Value of Volume of World Trade by Sea 2010’ (http://www.marisec.org/shippingfacts/worldtrade/volume-world-trade-sea.php) (10 Apr. 2012). ↩

- Graham Gerard Ong-Webb, ‘Piracy in Maritime Asia: Current Trends’ in Peter Lehr (ed.) Violence at Sea: Piracy in the Age of Global Terrorism (New York, 2007), p. 48. ↩

- Stefan Eklöf, Pirates in Paradise: A Modern History of Southeast Asia’s Maritime Marauders (Copenhagen, 2009), p. 48. ↩

- Eklöf, ‘The Return of Piracy’, p. 12. ↩

- Peter Earle, The Pirate Wars (London, 2003), p. 253. ↩

- The phrase ‘East of the Suez’ is derived from a poem written by Rudyard Kipling in 1890 entitled ‘Mandalay’: ‘Ship me somewheres east of Suez, where the best is like the worst, Where there aren’t no Ten Commandments an’ a man can raise a thirst…’. ↩

- P.L. Pham, Ending ‘East of Suez’: The British Decision to Withdraw from Malaysia and Singapore 1964-1968 (New York, 2010), p. 22. ↩

- The Straits Times, 15 Jan. 1968. ↩

- See: Eklöf, ‘The Return of Piracy’, p. 4. ↩

- Ong-Webb, ‘Piracy in Maritime Asia’, p. 47. ↩

- Also known as ‘Gulf of Siam’. ↩

- Peter Chalk, ‘Contemporary Maritime Piracy in Southeast Asia’ in Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, vol. 21, no. 1 (Sept. 1998), p. 89. ↩

- US Library of Congress, Federal Research Division, ‘Country studies (1988-98)’ (http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/cshome.html) (9 Oct. 2012). ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Chia Lin Sien, ‘The Importance of the Straits of Malacca and Singapore’ in Singapore Journal of International & Comparative Law, no. 2 (1998), pp 305-6. ↩

- Warren, ‘A Tale of Two Centuries’, p. 9. ↩

- Peter Chalk, Non-Military Security and Global Order: The Impact of Extremism, Violence and Chaos on National and International Security (London, 2000), p. 76. ↩

- Samuel P. Menefee, ‘Violence at Sea: Maritime Crime and the Rise of Piracy’ in Jane’s Defence 1997: The Yearbook for Jane’s Defence Magazines (1997), p. 100. ↩

- Peter Chalk, ‘Contemporary Maritime Piracy in Southeast Asia’, p. 94. ↩

- Jon Vagg, ‘Rough Seas? Contemporary Piracy in Southeast Asia’ in British Journal of Criminology, vol. 35, no. 1 (Winter 1995), pp 76-7. ↩

- See: Pascal Boulanger, ‘The Gulf of Thailand’ in Eric Ellen (ed.) Piracy at Sea (London, 1989), p. 87. ↩

- San Diego Union, Feb. 2 1980. ↩

- Nhat Tien, Duong Phuc & Vu Thanh Thuy, Pirates on the Gulf of Siam: Report from the Vietnamese Boat People Living in the Refugee Camp in Songkhla – Thailand (California, 1981), p. 112. ↩

- ‘Letter from the office of the Prime Minister, government house, Bangkok to Dr. Ven Thich Man Ciac’ 10 April, 1980 (Nhat Tien et al., Pirates on the Gulf of Siam, app. ii). ↩

- G.V.C. Naidu, ‘ASEAN Navies in Perspective III’ in Strategic Analysis, vol. 21, no. 7 (Oct. 1997), p. 1061. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Villar, Piracy Today, p. 131. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- ‘Piracy Statistics: Thailand (based on refugee reports)’ in Eric Ellen (ed.) Piracy at sea (London, 1989), pp 282-85. ↩

- In 1981: Boats arrived = 452, Boats attacked = 349, No. of attacks = 1122 => No. of attacks per attacked boat = 3.2; See: Ibid. ↩

- Villar, Piracy Today, pp 137-8. ↩

- See: ‘Letter from US Department of State, office of Asian Refugees to the President of the Boat People SOS Committee’ 15 June, 1980 (Nhat Tien et al., Pirates on the Gulf of Siam, app. xii). ↩

- W. Courtland Robinson, Terms of Refuge: The Indochinese Exodus and the International Response (London, 1998), p. 167. ↩

- Robinson, Terms of Refuge, p. 167. ↩

- Harry C. Blaney III, ‘Anti-Piracy in Southeast Asia: US and International Efforts and Programmes’ in Eric Ellen (ed.), Piracy at Sea, p. 102. ↩

- Nhat Tien et al. Pirates on the Gulf of Siam, p. 29. ↩

- See: Joachim Henkel, ‘Refugees on the High Seas: A Dangerous Passage’ in Eric Ellen (ed.), Piracy at Sea, p. 108. ↩

- Villar, Piracy Today, p. 36. ↩

- ‘Piracy Statistics: Thailand’. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- ‘Piracy Statistics: Thailand’. ↩

- I.R. Hyslop, ‘Contemporary Piracy’ in Eric Ellen (ed.) Piracy at Sea (London, 1989), p. 36. ↩

- ‘Summary of Arrests, Prosecutions, Convictions and Sentences in Thailand for Piratical Offences against Boat People 1982-87’ in Eric Ellen (ed.), Piracy at Sea, p. 286. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- ‘Opening Statement by Mr. Poul Hartling, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, to the Executive Committee of the programme of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, thirty-sixth session, Geneva’ (7 Oct. 1985). ↩

- UNHCR, ‘Guidelines for the Disembarkation of Refugees’ (1985), p. 4. ↩

- ‘Opening Statement by Mr. Poul Hartling’ (7 Oct. 1985). ↩

- Hyslop, ‘Contemporary piracy’, p. 37. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, The State of the World’s Refugees 2000: Fifty Years of Humanitarian Action (New York, 2000), p. 87. ↩

- Robinson, Terms of Refuge, p. 171. ↩

- UNHCR, State of the World’s Refugees 2000, p. 87. ↩

- ICC International Maritime Bureau, Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships: Annual Report, 1 Jan. – 31 Dec. 2002 (London, 2003), p. 5. ↩

- IMO, Resolution A.683 (17) (21 Nov. 1991), pp 1-2. ↩

- IMO, A 17/ Res. 683, p. 2. ↩

- Eklöf, Pirates in Paradise, pp 136 & 149. ↩

- See: New Straits Times, 29. Oct. 1992. ↩

- Susumu Takai, ‘Suppression of Modern Piracy and the Role of the Navy’ in National Institute for Defence Studies, Journal of Defence and Security: Security Reports, no. 4 (March 2003), p. 54. ↩

- Yann-huei Song, ‘Regional Maritime Security Initiative (RMSI) and Enhancing Security in the Straits of Malacca: Littoral States’ and Regional Responses’ in Shicun Wu & Keyuan Zou (eds.) Maritime Security in the South China Sea: Regional Implications and International Cooperation (Surrey, 2009), p. 120. ↩

- Susumu Takai, ‘Suppression of Modern Piracy’, p. 54. ↩

- See: Chalk, ‘Contemporary Maritime Piracy in Southeast Asia’, p. 100. ↩

- IMO, Resolution A.738 (18) (4 Nov. 1993), p. 1. ↩

- ICC IMB, Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships: Annual Report 2002, p. 5. ↩