“…the Marine Corps is in serious trouble…The brutal truth is that a growing number of defense analysts regard the Marine Corps as an under-gunned, slow-moving monument to a bygone era in warfare.”

– William Lind and Jeffrey Record, 1978

Since the Persian Gulf crisis erupted, there has been an increased interest and growing recognition of Marine Corps capabilities. Because of our readiness and ability to deploy quickly to the scene of a crisis, we can expect to assume an even greater role in the defense of our nation in the years ahead…I view the decade of the 80s as an opportunity for our Corps to demonstrate its unique capabilities to the Nation and make a significant contribution to national security.

– Commandant Robert Barrow, 1980

Contents:

Roles and Missions

Outside Critics

Why a Marine Corps?

Shifting Strategic Priorities

The Marine Corps and the Rapid Deployment Force

Conclusion

By Nathan Packard

Fleet Seminar Professor, Naval War College

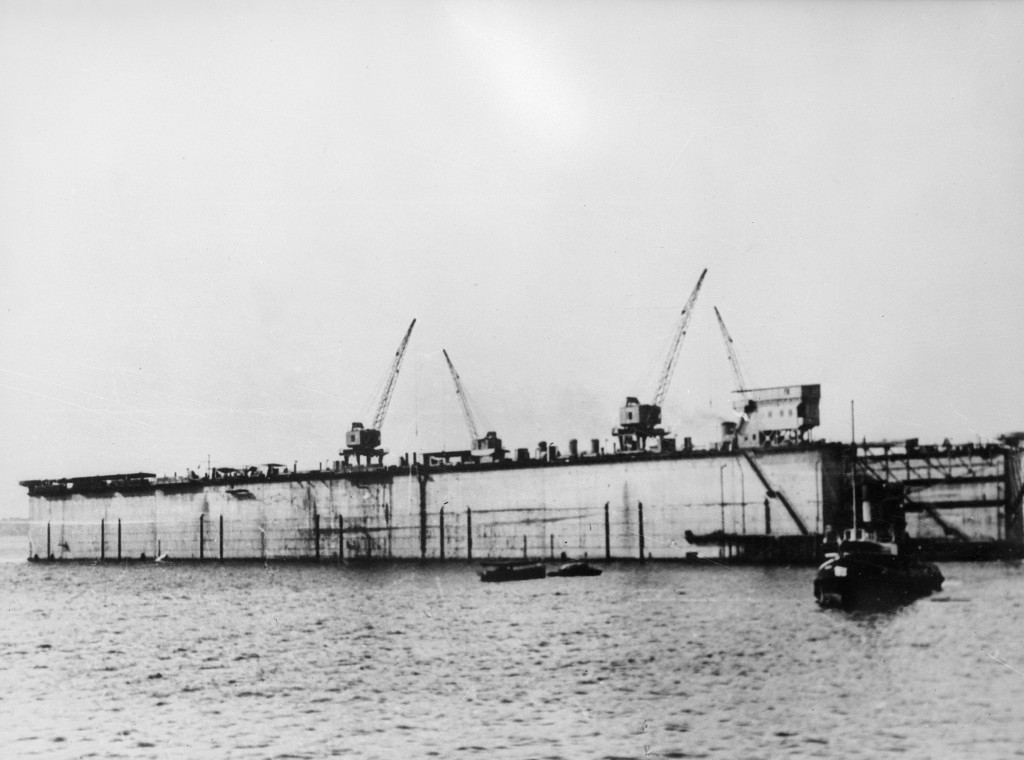

WILMINGTON, NC (July 3, 1980) U.S. Marine Corps’ M-60A1 tanks await loading on USNS MERCURY (T AKR 11), a roll-on, roll-off ship of the Navy’s Military Sealift Command, during Leading operations this week. (Photo by PH3 George Bruder, USN/DoD Image)

In the aftermath of the Vietnam War, the Marine Corps was a service in search of a mission. Traditionally, it had justified its existence by highlighting its capabilities as a rapid response force for Third World contingencies and as amphibious shock troops in the event of a conventional war. The American people, however, had little appetite for interventions following the recent experience in Southeast Asia. Likewise, a massed amphibious assault – the Marine Corps’ raison d’etre since the interwar period – was considered highly unlikely in a war with the Soviet Union. Thus, by the mid-1970s, there were on-going discussions within the Department of Defense, Congress, and the media about the future role of the Marine Corps. Critics referred to it as an anachronism and “a dinosaur which had outlived its usefulness.”

Ultimately, events in the Middle East – specifically the Iranian Revolution and hostage crisis and the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan in 1979 – provided the Marine Corps with a new strategic purpose. In his 1980 State of the Union Address, President Carter made it clear that Washington was prepared to use military force to defend U.S. interests in the Persian Gulf. Sensing an opportunity, the Marine Corps adapted its capabilities to the strategic goals outlined in the Carter Doctrine. This article examines how the Marine Corps made the case for its continued relevance by offering itself as the solution to one of the nation’s most vexing foreign policy challenges – ongoing instability in the Middle East.

Roles and Missions

In 1954, Samuel Huntington coined the term “strategic concept” to refer to a military service’s roles and missions relative to national policy objectives. The concept described “how, when, and where the military service expects to protect the nation against some threat to its security.” Absent a compelling concept, a service “becomes purpose-less, it wallows about amid a variety of conflicting and confusing goals, and ultimately it suffers both physical and moral degeneration.” Its efforts lack unity of purpose and as an institution it is unable to convince society to commit the resources required to maintain it. A service must be able to answer the following question: “What function do you perform which obligates society to assume responsibility for your maintenance?” A strong strategic concept has been especially important for the Marine Corps. Unlike the Army or Navy, it could not point to the militaries of potential adversaries to justify its existence. Most countries did not maintain a Marine Corps.

As outlined in the National Security Act of 1947, the primary mission of the Marine Corps was to prepare for and execute amphibious landings. In subsequent legislation Congress solidified the Corps’ amphibious orientation and mandated a permanent force structure of at least three active amphibious assault divisions and three air wings. The National Security Act and the debates and reports surrounding it also reaffirmed the Corps’ secondary role as a crisis response force. The Act stipulated that the Corps be prepared to “perform such other duties as the President may direct.” In practice, this meant the service could be used by the executive branch to resolve situations that fell in the gray area between diplomacy and war.

The legislative protections outlined above ensured the Marine Corps’ survival in the defense unification debates that followed the Second World War; however, amphibious assaults seemed to have little place in the strategic context of the 1970s. The other services rebounded from the Vietnam War by re-focusing on their enduring responsibilities with respect to the Soviet Union. Unfortunately for the Marine Corps, its strategic concept was better suited to an island-hopping campaign against Japan. Because Soviet power was primarily land-based, U.S. war plans, should the Cold War go hot, minimized the role of maritime forces and relegated amphibious operations to diversionary attacks on flanks of the Eurasian landmass.

In 1971, Commandant Leonard F. Chapman predicted that “the golden age of modern amphibious warfare is still in the future,” but some Marines were skeptical. Retired Colonel James Donovan, for example, a decorated veteran of World War II, regarded basing force structure, doctrine, and budget requests on an old mission as a clear case of “strategic regression.” The Marine Corps was focusing on the type of war it wanted to fight rather than the one it was likely to fight. Over the long term, trying to perfect Iwo Jima-style assaults would drain limited resources and serve as a drag on innovation.

Similarly, the promulgation of the Nixon Doctrine as the Vietnam War was winding down sent a clear signal that the White House had little interest in Third World interventions. In his 1970 State of the Union Address, President Richard Nixon informed allies that in the future they would bear primary responsibility for their own security. The President’s pledge to “reduce our involvement and our presence in other nations’ affairs,” accurately reflected the national mood after five years of war. Such pronouncements did not bode well for a service that had long been policymakers’ force of choice for armed involvement in the internal affairs of other countries. Congress also took steps to limit presidential latitude in the use of force with the War Powers Resolution of 1973, which required congressional approval for the commitment of U.S. forces to combat abroad. The general reluctance to use force often referred to as the Vietnam Syndrome discredited one of the Marine Corps’ historic missions.

For the armed services, roles and missions are of the utmost importance; it is how they lay claim to their portion of the defense budget. With one of its primary missions considered antiquated and the other distasteful, the Marine Corps would be hard-pressed to justify its budget requests during the lean years of the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations.

In general, the period 1972 to 1979 was the most austere in terms of defense budgets since World War II. Although the post-Vietnam drawdown in some ways resembled the typical boom and bust cycle associated with a nation shifting from war to peace, the situation was exacerbated by the weakened state of the domestic economy. In terms of economic performance, the 1970s was the worst decade for the U.S. economy since the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Dow Jones Industrial Average plummeted from 1000 to 577 from 1972 to 1974 and would not hit 1000 again until late 1982. The economy was plagued by stagflation, a situation in which rising unemployment was paired with high inflation. Both the inflation rate and the unemployment rate hovered around nine percent in the mid-1970s. Domestic economic woes not only affected standards of living and the national mood – contemporary commentators referred to the 1970s as an “Age of Limits” and an “Era of Decline” – they also affected the defense budget. While the administrations of Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford sought to slow the growth of defense spending, Jimmy Carter came into office pledging to cut billions of dollars in defense spending. The combination of double digit inflation and spiraling fuel costs made the 1970s some of the most austere years in U.S. history in terms of defense buying power.

In a 1985 report, Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Burns used fiscal data to quantify the impact of stagflation on the Marine Corps. He focused primarily on the Operations and Maintenance and Ground Force Procurement Appropriations. These were the two areas of the budget over which Headquarters Marine Corps had the most discretion when it came to actual spending. These were the funds used to buy equipment, maintain facilities, and conduct training exercises. Burns calculated that between FY 1977 and FY 1980, the Operations and Maintenance budget had increased by roughly 46 percent, from $594.365 million to $872.59 million. The large increase kept it just slightly ahead of inflation. The Ground Force Procurement Appropriation, on the other hand, had decreased by 13 percent during the same period. Under Secretary of Defense Harold Brown, the service saw its procurement budget drop from $326.7 million in FY 1977 to $283.785 million in FY 1980. Secretary Brown also refused to fund the construction of any new amphibious ships or the procurement of the AV-8B Harrier aircraft, the Marine Corps’ top aviation priority.

Burns’ findings supported a 1979 report by the U.S. Comptroller General, which had concluded: “Since 1970, the Marine Corps budget has increased only about 25 percent in actual dollars, which represents a decrease in purchasing power of about 30 percent in 1979 constant dollars.” Simply put there was less money to go around and what money there was bought less and less each year.

Outside Critics

As budgets tightened, criticism of the Marine Corps intensified. Most worrisome were critiques on the part of Congressmen and members of their staffs. Historically, Congress had been a long-time ally of the Corps and repeatedly protected it against budget cutters in the executive branch. By the mid-1970s, however, even many of the Corps’ friends in both Congress and the media believe that the service’s roles and missions had become disconnected from the nation’s actual defense needs. The message was plain – the Marine Corps must adapt to present realities or run the risk of strategic irrelevance.

According to Allan Millett, the foremost historian of the Marine Corps and a serving officer during the period in question, critics advanced six arguments: (1) the U.S. military was unlikely to get involved in conflicts outside of the European theater (2) amphibious forces had little utility in a war with the Soviets (3) the Marine Corps lacked the mechanized forces required on the modern battlefield (4) the Marine air component was vulnerable to sophisticated air-defense systems (5) the Corps had little to offer NATO, moreover, integrating the service into existing NATO plans would prove difficult, and (6) due to budget constraints the Navy would not make the construction of amphibious shipping a priority.

During the period of 1975 to 1978, defense analysts William S. Lind and Dr. Jeffrey Record offered the most cogent analysis of the Marine Corps’ shortcomings in articles and policy papers with provocative titles, such as Where Does the Marine Corps Go from Here? and “Twilight for the Corps?” Lind and Record, both congressional staffers who worked military issues in the U.S. Senate, reiterated their arguments in a white paper endorsed by Senator Robert Taft, Jr. (R-OH). In 1978 the paper was reissued with the endorsement of Senator Gary Hart (D-CO). Bi-partisan support for statements such as, “The maintenance of almost 200,000 men in an obsolescing force structure cannot be justified,” caught the attention of Marines at all levels.

Lind and Record’s analysis relied heavily on the 1973 Arab-Israeli War as a template for future wars. Fought from October 6 to 25 of that year, the conflict pitted a coalition of Arab states led by Egypt and Syria against Israel. It involved thousands of state of the art tanks and sophisticated fighter aircraft maneuvering rapidly on and above the battlefield. From their study of the conflict, Lind and Record concluded that future wars would be quick, technologically intensive affairs defined by the rapid movement of heavily mechanized forces. In their opinion, the Marine Corps was ill-suited for this type of conflict for two reasons. The first was that the Marine Corps’ amphibious ships would never have gotten them to the war in time. Second, even if they were able to get to the fight, they lacked the armor needed to win on the modern battlefield. Consequently, according to Lind and Record, “[t]he brutal truth is that a growing number of defense analysts regard the Marine Corps as an under-gunned, slow-moving monument to a bygone era in warfare.”

The first challenge fell under strategic mobility – how the Corps planned to get to the fight. Lind and Record believed the “principal issue confronting the United States Marine Corps today is the future viability of the amphibious mission.” America’s most dangerous adversaries, the Soviet Union and, to a lesser extent, China were land powers whose vast territory and large armies offered few opportunities for a decisive amphibious assault. In a war with either power, amphibious operations would serve as little more than a diversion. In addition, the concentration of forces required during the ship-to-shore movement phase of a landing, made such forces vulnerable to precision-guided weapons. Most importantly, the limited quantity of amphibious ships and their slow rate of speed called into question the Marine’s utility as a crisis response force.

Criticism of the amphibious mission was echoed by senior administration officials. For example, in 1974, Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger commissioned a series of studies that asked, among other things, why have a Marine Corps? In 1975, he expressed his doubts about amphibious ship-building programs in his annual report to Congress:

[Our] amphibious forces are not cheap….These programs, their costs, and the delays that have attended their completion have raised questions about the need for an amphibious assault force which has not seen anything more demanding than essentially unopposed landings for over 20 years, and which would have grave difficulty in accomplishing its mission of over-the-beach and flanking operations in a high-threat environment.

Later that same year, the Senate Armed Services Committee, which had historically been friendly to the Corps, directed that the service conduct a complete review of its force structure and manpower situation. The shortage of amphibious shipping led Senator Sam Nunn, previously a strong supporter of the Corps, to doubt the service’s ability to get to the fight: “If the U.S. Marine were called upon to undertake a major landing in the Persian Gulf or elsewhere in the Middle East, they would probably have to walk on water to get ashore.” The relative slowness of amphibious transit was highlighted in a 1976 report by the Congressional Research Service which concluded that shortages in amphibious shipping would result in a two-month lead time to launch a division-sized operation.

By the mid-1970s there was a widespread belief within defense circles that the Marines were too slow to give the White House the responsiveness it desired. Transit times via amphibious shipping from the United States to potential trouble spots in Asia and the Middle East were anywhere from one to two months. Critics charged that the window for action would close before Marines could arrive in sufficient numbers to advance U.S. interests. Thus, amphibious capabilities were a low priority in a time of tight defense budgets. Such doubts were expressed in the declining share of the budget devoted to Marine Corps programs. The 1979 defense budget, the first produced entirely by the Carter Administration, was a prime example. The Marine Corps’ funding request for the Advanced Harrier (AV-8B) program, its top aviation priority, was cut from $173 million to $85 million. The administration also pushed back the planned procurement of a new dock landing ship (LSD-41) from FY 1979 to FY 1981. Although Secretary Brown testified that delays to both programs would produce design efficiencies over the long-term, it is telling that in a budget that discussed only three Marine-specific programs at length – the AV8-B, the LSD-41, and the Landing Craft Air Cushion (LCAC) – two of the programs were being cut or delayed.

Furthermore, even if the Marine Corps possessed the strategic mobility needed to get to a conflict, it lacked the firepower, armor, and tactical mobility needed to fight and win on the modern battlefield. Here again, the service was limited by its amphibious orientation. In order to get everything it needed aboard ships, it was constructed primarily around three divisions of light infantry. Although the Corps possessed three tank battalions of 55 tanks each, these were employed in a supporting role not as an independent maneuver element. Furthermore, the tanks, M-48s and M-103s, were nearly two decades old. In addition, the service had hundreds of armored amphibious tractors for transporting troops. Because of the need to operate on both land and sea they were inherently inferior to infantry fighting vehicles developed for land use only.

By comparison, while the Corps had spent nearly a decade focused on counter guerilla operations in the jungles of Southeast Asia, modern militaries had become increasingly mechanized. By the mid-1970s the U.S. Army, America’s NATO allies, as well as likely adversaries, namely the Soviets and Warsaw Pact countries, employed tank formations to spearhead advances; infantry and supporting elements rode in mechanized vehicles configured specifically for high rates of speed and mobility, a style of warfare reminiscent of the German Blitzkrieg of World War II. In such a conflict, the Marine Corps would have difficulties integrating with allies as well as engaging the enemy. Once again, the 1973 Arab-Israeli War was a case in point. During a little more than two weeks of fighting, the two sides lost somewhere in the neighborhood of 3,000 tanks, nearly six times more than the Marine Corps had in its entire inventory. By the mid-1970s, many Third World militaries possessed the economic resources required to field several mechanized divisions. Consequently, though Lind and Record concluded that the best use for the Marine Corps might be to focus it on Middle East contingencies, it would be at a serious disadvantage in that region as well. As of 1978, the Corps had 238 tanks in active service as compared to Iran’s 3,200, Egypt’s 1,930, Syria’s 2,600 and Iraq’s 1,500. Based on these numbers it appeared that the Marine Corps was headed towards “comparative impotence.” It lacked the firepower and mobility needed to win on the modern battlefield.

As a solution to the service’s ills, Lind and Record suggested that the Marine Corps focus exclusively on Third World contingencies and that it organize and equip itself as a first-rate mechanized force. The relative slowness of sea transit could be overcome through the prepositioning of supplies, the forward deployment of forces, and an increased reliance on air transport. In the event that the President called for an overseas intervention, the overall concept involved forward-deployed Marine amphibious units and air-mobile contingents serving as the lead elements. The lead contingent would be reinforced by heavier forces whose personnel would arrive via plane and marry up with prepositioned equipment or be transported to the area by amphibious shipping. Thus, the Marine Corps would be structured so as to offer “a new capability to project a quick-reaction insertion-capable force able to defeat mechanized opponents in mobile warfare.”

Why a Marine Corps?

As a result of critics such as Lind and Record and misgivings over the Vietnam War, the 1970s was a period of intense institutional self-examination on the part of the Marine Corps. General Anthony Zinni, a junior officer at the time who would command Central Command in the late 1990s, recalled “in 1974, ’75, and ’76, those of us within the Marine Corps recognized that we had to change. The battle was over how.” Debates were on-going and took place in various forums, both formal and informal. Marines ranging in rank from sergeant to general let their views be known on the pages of the Marine Corps Gazette and in other defense-related publications. In articles, speeches, and Congressional testimony, Marines made their case for why the nation should maintain a Marine Corps and what such a force should look like in the future. In so doing, the service tried to match its traditional missions to the current strategic context.

In 1975, Commandant Louis Wilson convened the Haynes Board to “develop alternative force structures, concepts of employment, and disposition and deployment of Marine Corps forces through 1985.” The Haynes Board Report provided a synopsis of how the Marine Corps envisioned its role within the national security establishment in the mid-1970s. Completed in 1976 and named for Major General Fred E. Haynes, Jr., the chair of the board, the report reinforced traditional roles while also recommending sweeping changes. It reaffirmed the basic structure of three active divisions and wings as well as the service’s naval character and amphibious orientation.

However, the board repeatedly recommended that the Marine Corps shift from low intensity conflict in Asia to mid to high intensity conflicts in Europe and the Persian Gulf. Like Lind and Record, the authors of the report concluded “today’s Fleet Marine Forces should be organized, trained, and equipped to engage an armor-heavy enemy in other than defensive combat.” Furthermore, each of the three alternative force structures they recommended called for increased firepower and mobility. The report envisioned tanks as “a ground-gaining maneuver element,” procurement of a dedicated infantry fighting vehicle, and improved antitank capabilities.

The Haynes Board Report, along with a plethora of articles and speeches by senior Marines, made it clear that the Marine Corps would base its future relevance on being the nation’s amphibious force in readiness. First, geography made the need for expeditionary forces obvious. Other than a conflict with Mexico or Canada, any future conflict would involve sending U.S. forces overseas. Furthermore, in the event of a war with the Soviets, the seizure of geographic choke points such as the Suez Canal, the Straits of Hormuz, or the Straits of Malacca would be critical. Second, amphibious forces could hover offshore and be inserted and extracted quickly, giving policymakers a degree of flexibility not offered by other forces. Their mode of transit eliminated the need for basing and over flight rights. Using the sea as maneuver space also generated uncertainty in the eyes of possible adversaries; until Marines actually landed it was hard to determine where they were headed. Third, amphibious forces offered a forcible entry capability and could fight their way ashore if necessary. Fourth, amphibious forces were equally comfortable on land, on sea, or in the air, thus they could bridge the gaps that existed amongst the other services which tended to think in terms of a single domain. Commandant Wilson summed up the Marine Corps’ collective response to those who considered amphibious operations outdated when he told an interviewer, “critics had said that before. They were wrong then and just as wrong now.”

The Haynes Board recommended updating the definition of “amphibious operations” to bring it more in line with what Marines were doing in the latter half of the 20th century. It was not so much that the concept was antiquated, but rather, that critics had an antiquated conception – think Sands of Iwo Jima – of amphibious operations. To start, the definition in joint doctrine should be changed from:

An attack launched from the sea by naval and landing forces, embarked in ships or craft involving a landing on a hostile shore.

To the more inclusive, but far wordier:

Operations conducted from the sea by naval and landing forces for the purpose of projecting US influence ashore into either a hostile or non-hostile environment. Amphibious operations can be conducted during peacetime, threatening crisis or war, to achieve political, military, and/or economic aims and may involve the landing of selected or total elements of the force, or an amphibious demonstration without landing.

Such a definition would cover the full range of military operations from general war to the evacuation of U.S. citizens and disaster relief.

Throughout the latter half of the 1970s, the Marine Corps spoke with a common voice regarding the strategic advantages of amphibious forces. By 1980, Headquarters Marine Corps had compiled and distributed to all general officers a four page list of talking points that not only refuted the various arguments against amphibious forces, but also offered no less than twenty possible scenarios that would require amphibious forces.

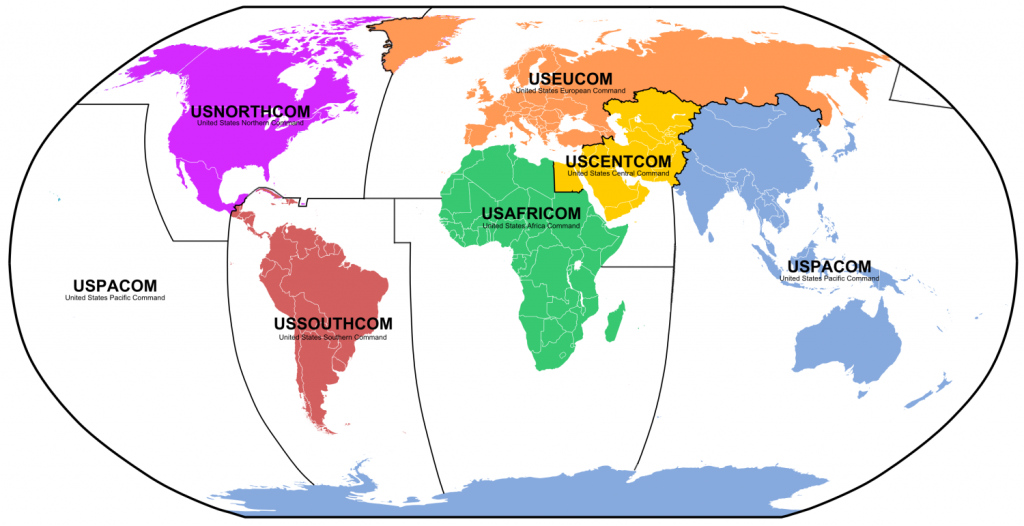

Central Command’s Area of Responsibility (AOR) in 1983 and 1989 (Courtesy Carolina Center for the Study of the Middle East and Muslim Civilizations)

Likewise, senior Marines refined and defended the force in readiness portion of their mission. According to General Haynes, while his team identified much room for improvement, the nation needed a crisis response force and Marines were the best candidates. General Haynes concluded, “the corps’ overall philosophy – i.e., seeing itself as posture for contingencies anywhere on the globe, with flexibility of force and a high degree of readiness – has remained unchanged and sound.”

Marines believed effective diplomacy required credible military force to back it up and U.S. interests required protecting, often on short notice. As such, they had long billed themselves as most ready when the nation was least ready. In 1978, for example, Commandant Louis Wilson told Congress, “[o]perational readiness is at the apex of our efforts. It is the cornerstone of our existence as a fighting military organization.” In simple terms, military readiness was nothing more than a unit’s capacity for executing an assigned mission in a timely manner. The Corps’ focus on readiness was evidenced in its force laydown, expeditionary mindset, and principal organization – the air-ground task force.

In terms of force laydown, the Marine Corps was divided into three Marine Amphibious Forces (MAFs); one each on the East Coast, West Coast, and in Okinawa, Japan. Thus, it was well-positioned to access the oceans and continents of the world. Furthermore, since World War II, the Corps had contributed to the nation’s “forward defense” strategy by permanently maintaining smaller Marine Amphibious Units (MAUs) of approximately 2,000 Marines each; aboard ships in the Caribbean, Western Pacific, and Mediterranean seas. Along with aircraft carrier strike groups, MAUs were often the first entities Washington turned to when it sought to project power abroad or resolve a crisis short of war. The national command authority could order MAUs moved as it saw fit or instruct the Corps to reinforce them by means of a Marine Amphibious Brigade (MAB) or even the entire MAF. Of the options provided by amphibious forces afloat, General Al Gray, who would go on to become Commandant in 1987 said, “If the Navy and Marines had an amphibious task force off Norfolk one night, we could land anywhere from Long Island, New York, to Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, the next morning.”

As for the Corps expeditionary mindset, Marines dating back to the turn of the 20th century had prided themselves on being able to pack-up and ship-out on short notice. Everything Marines own can be packed up and put aboard ship. On this topic, General Zinni remarked:

We are by our nature “expeditionary.” This means several things. It means a high state of readiness; we can go at a moment’s notice. It means our organization, our equipment, our structure, are designed to allow us to deploy very efficiently. We don’t take anything we don’t need. We’re lean. We’re slim, we’re streamlined.

By comparison, the U.S. Army of the 1970s was very much a garrison force geared towards permanently stationing large units where they were expected to be employed. In the aftermath of Vietnam, the Army organized itself around conventional armored warfare on Europe’s central front. It wanted nothing to do with messy Third World conflicts and turned its back on contingency operations. Thus, the Marine Corps stood ready to do what the Army did not want to do. While Marines were certainly not satisfied with the experience of Vietnam, they recognized that these missions were not going away and stood ready to execute them.

Furthermore, the Marine Corps’ principal organization, the Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF; pronounced mag-taff), was designed with rapid response in mind. MAGTFs grouped an air combat element, a ground combat element, and a combat service support element under a single commander. They were flexible in that while the basic organization remained the same, the number, size, and types of units in each of the core elements could be adjusted based on mission requirements. They could also be formed, reinforced or disbanded on short-notice. Integrating air and ground forces under a single commander enhanced combat effectiveness and proved remarkably versatile and responsive. According to one former commandant writing in 1976, MAGTF’s “represent the nation’s – and the world’s – only truly balanced ready force of combined arms, whose air and ground components are linked by training and tradition and are ready without lost motion or time-consuming last minute preparations.” No inter-service coordination was required. Ultimately, the MAGTF construct ensured that the Marine Corps could respond to contingencies across the range of military operations.

In the process of responding to their critics, the Marine Corps leaders refined and articulated what it was they wanted their service to be, namely, “an elite air-ground force capable of global deployment”. Nevertheless, a clear sense of purpose was not enough to free up scarce dollars during the first three years of the Carter Administration. According to one Marine general, “you couldn’t sell the need for global power projection in the Pentagon prior to events in Iran, Afghanistan, and Nicaragua in 1979.” It would take a major reorientation of national security policy for the Marine Corps to match its capabilities to strategic needs and get the dollars flowing again. The service would find its mission in the chaos and disorder of the Middle East.

Shifting Strategic Priorities

In the realm of national strategy, the Marine Corps’ main challenge in the mid-1970s lay in the fact that its capabilities were not matched to a specific adversary or problem set, as had been the case with Japan in the 1930s. The situation changed dramatically in the late 1970s. Following the withdrawal of the British from their positions east of the Suez in 1971, the U.S. had relied on Iran to maintain stability in the Middle East. Civil unrest in that country beginning in 1978 eventually led to the fall of the Shah in early 1979. U.S. strategy was in disarray. Later, in December of that same year, at a time when 52 Americans were being held hostage in Tehran, the Soviet Union dispatched troops to Afghanistan. To U.S. policymakers, it appeared that the Middle East, a region whose oil supplies were vital to the West’s economy, was spinning out of control. To make matters worse, Washington was powerless to do anything about it.

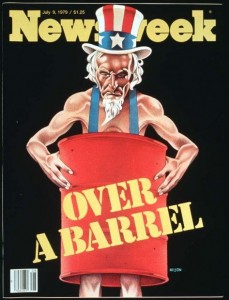

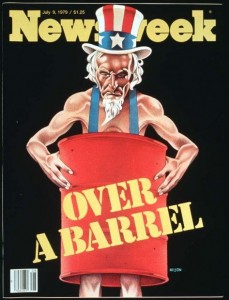

Newsweek Cover – July 9, 1979 (via Newsweek/TheBlaze)

The United States’ involvement in the Middle East had deepened over the course of the 20th century, mainly due to the region’s vast supplies of oil. The economic and strategic importance of Middle East oil cannot be overstated. In the opinion of Daniel Yergin, a leading historian of the oil industry, “oil has meant mastery throughout the twentieth century” because those who possessed it were often able to translate it into military, economic, and political power. Modern warfare became totally dependent on oil and the internal combustion engine in the first half of the 20th century. By the 1970s, all major weapons systems, save nuclear powered carriers and submarines, ran on oil. Oil was equally important to the civilian economies of industrial nations. Following World War II, oil fueled nearly two decades of economic growth in the United States and Western Europe, leading one British official to refer to it as “the lifeblood of the economy;” while another regarded fossil fuels as “not ‘just another commodity,’ but the precondition of all commodities, a basic factor equally with air, water, and earth.” As result of its strategic and economic importance, ensuring access to oil was one of the top concerns of U.S. policymakers.

The oil crisis of 1973 to 1974 highlighted the degree to which the United States and other industrial nations had come to depend on the unimpeded flow of Persian Gulf oil. U.S. domestic oil production peaked in 1970. With consumption on the rise, the United States had to import more and more oil to meet ever-growing demand. U.S. imports rose from 23.2 percent in 1970 to 36.3 percent in 1973; at a time when the Middle East was providing 40 percent of total world supply. In response to Washington’s support for Israel in the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) embargoed oil shipments to the United States and other Western nations, and cut production. The result was a quadrupling of oil prices. Another outcome of the crisis was that Western oil companies were forced to cede control of production and pricing to producing countries. Based on the 1973-74 oil crises, a number of observers concluded that the economic balance of power was shifting in favor of the developing world. The price of oil skyrocketed from $3.29 in 1973 to $11.58 in 1974. As the price of oil rose, so too did the prices of all petroleum based products from gasoline to plastics.

Beginning in earnest in 1974, many scholars, business leaders, and policymakers in the U.S. suggested using military force to ensure the flow of oil. Frustrated by America’s apparent weakness, they recommended military solutions. That these suggestions were being made so soon after Vietnam shows the degree to which rising energy prices negatively affected the domestic economy. In 1974 for example, Maxwell Taylor, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, cited the need for “flexible conventional forces” and “the threat or application of discriminating force” to deal with oil crisis-type scenarios. Pieces appeared in journals ranging from the left-leaning Harper’s to the conservative Human Events advocating the seizure of Arab oil fields by force. As the decade wore on and the U.S. economy continued to sputter, arguments for the use of force abroad to serve economic ends became more sophisticated and predictions increasingly dire. A 1977 RAND report drew heavily on world-systems analysis to explain the interconnectedness of the global economy and the possibility that it would break down if the U.S. did not use force to manage it.

Unrest in Iran increased tensions in the Middle East, as did growing Soviet involvement. Iran had for two decades been one of America’s closest allies in the region and a leading oil producer. Occupied as it was with the Vietnam War, the administration of President Richard Nixon adopted a “Twin Pillars” strategy for maintaining stability in the Middle East. Nixon’s strategic vision called for regional actors to bear primary responsibility for their own defense. In the case of the Middle East, those pillars were Saudi Arabia and Iran, both of which received sizable arms transfers as well as other military and economic aid from the United States. Of the two, however, Iran was by far the senior partner. Between FY 1950 and FY 1977, the Shah’s government purchased $10.7 billion in U.S. arms under the Foreign Military Sales Program, making Iran America’s number one arms customer during the period. According to a 1979 report by the Policy Studies Institute, the arms transfers accelerated under the Nixon Doctrine, with the President giving the Shah a “virtual carte blanche to purchase anything in the US arsenal except nuclear weapons.” Deliveries rose from $215 million in FY 1972 to a high of $2.8 billion in FY 1977.

The weakness of the strategy became apparent, however, when long simmering discontent with the Shah’s rule erupted into widespread civil unrest in early 1978. With the country paralyzed by strikes and demonstrations, the Shah and the Iranian military became internally focused. At roughly the same time that the situation in Iran was spinning out of the Shah’s control, pro-Soviet governments took power in Ethiopia, South Yemen, and Afghanistan, leading to increased Soviet military activity in the region, mainly in Ethiopia, the Red Sea, and the Gulf of Aden. From Washington’s perspective, it appeared Soviet influence was growing at the same time that its regional ally was barely hanging on. The situation came to a head in January 1979 when the Shah abdicated and fled the country; the radical Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini took power shortly thereafter and became head of a revolutionary government hostile to the U.S.

The political turmoil in Iran brought about a second oil crisis in 1979. The doubling of oil prices led to panic on the part of many U.S. consumers and long lines were seen at gas stations across the country. Between 1973 and 1979 the cost of oil per barrel had increased from $3.29 to $31.61. With the U.S. economy seemingly at the mercy of events in the Middle East yet again, calls for the use of force to ensure energy supplies reached a crescendo. One edition of Business Week depicted the Statue of Liberty in tears on its cover. In an article entitled, “The Decline of U.S. Power,” the author argued:

Now there are signs of U.S. weakness everywhere, and cracks are appearing in the system. The policies set in motion during the Vietnam war are now threatening the way of life built since World War II. The military retreat that began with the defeat of the U.S. in a place that held no natural resources or markets now threatens to undermine the nation’s ability to protect the vital oil supply and the energy base of the global economy.”

To many Americans, a more activist foreign policy was the obvious solution to ensure access to vital markets and raw materials. Inaction would risk a further reduction in America’s economic standing in the world.

By 1979, a consensus had developed amongst American policymakers and the general public in support of a more direct role for the United States with respect to stability in the Middle East. Appearing on Face the Nation, Secretary of Defense Harold Brown told viewers, “The United States is prepared to defend its vital interests with whatever means are appropriate, including military force where necessary, whether that’s in the Middle East or elsewhere” and oil “is clearly part of our vital interest…I said and I repeat, that in the protection of those vital interests we’ll take any action that’s appropriate, including the use of military force.” In congressional testimony, Secretary Brown compared the dangers of international economic disorder to the military threat posed by the Soviet Union. The notion that the United States was coming out on the losing end of a resource competition with the developing world was echoed in policy papers, speeches, and journal articles.

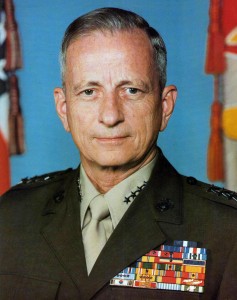

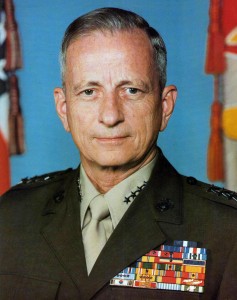

General Robert H. Barrow (USMC History Division)

Senior Marines wholeheartedly endorsed what Michael Klare, one of the few vocal critics of the approach, derisively referred to as the Brown Doctrine – military intervention as a means for dealing with disturbances in the global economy. In a draft speech, Commandant Robert Barrow referred to the “traditional ‘have-not’ nations” of the Third World that possessed “the raw materials that give the superpowers their strength…these ‘have nots’ no longer seem to be content with the status quo.” Although he held that these nations should be treated fairly, he posited naval forces as the ideal antidote to instability, since much of the Third World was accessible by sea. Junior officers echoed these assumptions in professional journals. According to one officer, “a lack of stability in distant parts of the world threatens the United States and, in our age of interdependence and transnational intercourse, also threatens global economic and security interests. Access to resources vital to our economy must be protected…a minimum world public and economic order system hinges upon stability.” Another general officer predicted chaos in Western Europe and Japan should the flow of Persian Gulf oil be interrupted. Such views would eventually be taken as a given in Marine Corps planning documents, one of which began with, “…the unimpeded flow of Persian Gulf oil to the world market is vital to the economic stability and national security of the US and its allies.”

In the spring of 1979, Carter’s National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski began pressing for a new security framework for the Persian Gulf. He envisioned something of enduring significance on par with the Truman Doctrine or NATO and called for a major strategic reorientation. In his estimation, America’s geostrategic concerns centered on three zones – Western Europe, Japan, and the Middle East – all of which were inextricably intertwined due to the first two being dependent on Middle East oil. That the latter region was part of what he considered an “arc of crisis” meant that it would require increasing involvement on the part of the U.S. going forward. Brzezinski went so far as to predict that, “[it] is very likely that in the 1980s we will be involved in an unprecedented effort to assure stability, and therefore exercise deterrence, in the Persian Gulf.”

The Carter Administration’s concerns were not new. Two years earlier, during an initial security review in 1977, the administration identified a need for enhanced power projection capabilities, specifically in the Persian Gulf and Southwest Asia. The report’s authors considered the Persian Gulf region a likely trouble spot and were greatly concerned that, according to one declassified top-secret memorandum, of all the regions of the world, “the U.S. would face the greatest difficulty projecting power in the Middle East.” It recommended the creation of a joint (four-service) force able to deploy rapidly in response to contingencies outside Europe and Korea. The outcome was Presidential Directive 18 (PD-18) which ordered the Department of Defense to “maintain a deployment force of light divisions with strategic mobility independent of overseas bases and logistical support…These forces will be designed for use against both local forces and forces projected by the USSR based on analysis of requirements in the Middle East, Persian Gulf, or Korea.”

What became known as the Rapid Deployment Force (RDF) never got off the ground, however, due to a lack of funding and disputes within the administration. According to historian Olav Njolstad, the initiative stagnated because the Department of State viewed the RDF as too provocative. For its part, the Department of Defense and the military services regarded it as a distraction and a drain on scarce resources. Although PD-18 is evidence that a shift was underway in U.S. defense priorities as early as 1977, at the time, according to William Odom, Brzesinki’s military assistant, the directive was simply ignored. Although the Secretary of Defense would eventually direct the services to establish a task force focused on Southwest Asia on October 22, 1979, it would take two additional crises to get the project moving.

The situation in Iran went from bad to worse on November 4, 1979, when Iranian students supportive of the Islamic revolution took dozens of American diplomats hostage. The hostage crisis brought to the fore America’s severely limited military options in the region. In response, Brzezinski initiated a Special Coordination Committee (SCC) called the “Persian Gulf Security Framework SCC.” The committee was tasked with finding ways to leverage America’s military, economic, diplomatic, and informational tools of national power to bring about favorable policy outcomes in the region. On Christmas Day 1979, only a few weeks after the formation of the committee, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan. Citing the need to defend a pro-Soviet Afghan government against rebels as justification, Soviet forces were in complete control of the Afghan government by December 28. The invasion completely changed the strategic equation. It provided a sense of urgency and enabled proponents of more robust military capabilities to overcome bureaucratic opposition. From Washington’s perspective, it appeared the Soviets were making a play for regional hegemony and control of the region’s oil resources.

President Carter laid out his administration’s response in his State of the Union Address delivered on January 23, 1980: “Let our position be absolutely clear: An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.” Furthermore, “We are also improving our capability to deploy U.S. military forces rapidly to distant areas.” The President regarded the invasion as a clear strategic threat that needed to be answered. He paired what became known as the Carter Doctrine with a request for increased defense spending of approximately $100 billion from 1981 to 1985, which he referred to “as a matter of fundamental policy.” The morning after Carter’s speech, the Washington Post referred to the oil wells of the Gulf as “the heartbeat of Western civilization,” and noted that “For the first time since the high point of involvement in the Vietnam war a decade ago, the United States is increasing its military forces and security commitment in a far-away region rather than reducing them.” The article went on to describe Pentagon officials working feverishly to address the challenges of projecting power into the Middle East.

In the minds of policymakers, the geostrategic stakes could not have been higher. In one speech, President Carter told listeners: “In recent years it’s become increasingly evident that the well-being of those vital regions [Europe and Japan] and our own country depend on the peace, stability, and independence of the Middle East and the Persian Gulf area. Yet both the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and the pervasive and progressive political disintegration of Iran put the security of that region in grave jeopardy.” The President’s sentiments were echoed by Secretary Brown in congressional testimony delivered in 1980: “what is at stake in the Persian Gulf is [the] economic and political well-being of the United States and its allies. If the industrialized nations of the world were deprived of access to the energy resources of the Gulf, the results…would very probably be [the] collapse of our allies and the world economy.”

Wreckage at Desert One, Iran (April 1980) where eight Americans died. (United States Special Operations Command History, 1987-2007)

At the time, however, the U.S. lacked the military capabilities needed to protect the interests identified by policymakers and to enforce the strategic commitments outlined in the Carter Doctrine. Prior to 1980, the United States had interests in the Middle East, but limited capacity for projecting force. In the mid-1970s, for example, the Chief of Naval Operations, after reviewing military options in the Middle East concluded: “It becomes evident that there is little we can effectively accomplish in M.E. [the Middle East].” This conclusion was borne out by the Desert One debacle, a failed attempt to rescue the hostages in Teheran that cost the lives of eight American servicemen in April of 1980. The operation highlighted shortcomings in the areas of logistics, equipment, training, and command arrangements. In order to reach Teheran, the mission had to fly over 1000 miles from an aircraft carrier and refuel multiple times. In the end, it had to be aborted because too many aircraft were lost during the transit phase. According to William Odom, the U.S. was simply “unprepared to conduct major military operations in Southwest Asia and the broader Middle East.”

To remedy this deficiency, a renewed emphasis was placed on the RDF. During Carter’s final months in office, his administration produced two policy documents that represented a shift in Washington’s approach to the Middle East: Presidential Directive 62 (PD-62) – “Modifications in U.S. National Security” and PD-63 “Persian Gulf Security Framework.” The former made it clear that a shift in strategic priorities had occurred. America’s allies in Europe in Asia would be expected to bear more of the burden while the U.S. redirected its attention to the Middle East. PD-62 also noted the need for increased spending on military readiness. One draft version stated, “the Persian Gulf shall have highest priority for improvement of strategic lift and general purpose forces in the Five Year Defense Plan.” For its part, the Persian Gulf Security Framework took things a step further by outlining a number of security initiatives – basing and over-flight agreements, combined exercises, arms transfers, a joint command responsible for the region, and a rapid deployment capability – to enhance U.S. military options in the region. Upon learning of these policy statements, one analyst concluded, “The essence of Carter’s plan, when stripped of its less-developed political and diplomatic elements, is to improve the U.S. ability to project and sustain military power in this far-away, yet vital, area.” In time, the U.S. would assume direct responsibility for ensuring stability in the region, becoming what one historian has referred to as the “guardian of the gulf.”

The Carter administration’s strategic pivot to the Middle East opened new opportunities for the Marine Corps. The service had long-prided itself on its readiness to conduct expeditionary operations. And while it had limited experience in the Middle East, the fact that much of the region was accessible from the sea played to the service’s amphibious orientation. Over the next several years, the Marine Corps would play a leading role in turning Carter’s strategic vision into a military reality. Senior Marines presented the service’s capabilities as the solution to the administration’s most vexing foreign policy challenge, how to project military force into the region.

The Marine Corps and the Rapid Deployment Force

After much prodding from the White House, on October 22, 1979, Secretary Brown finally directed the Joint Chiefs of Staff to establish a joint task force that would have operational planning, training, and exercise responsibility for rapidly deploying forces worldwide, but with a specific focus on Southwest Asia. On November 01, 1979, it was determined that the Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (RDJTF) would be a subordinate component of Readiness Command, the headquarters responsible for all general purpose forces based in the continental U.S. On March 1, 1980, the RDJTF headquarters was established at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida under the command of Marine Lieutenant General Paul. X. Kelley. The challenges facing the new command lay primarily in the areas of strategic mobility and sustainability. Unlike previous wars typified by incremental build-ups, the RDF concept called for introducing massive combat power in the initial stages of a crisis. Political considerations, however, precluded the stationing of large numbers of U.S. troops in the region. Thus, the bulk of the forces would need to come from the United States. The central question was how to quickly transport tens, perhaps even hundreds, of thousands of combat ready troops to an area literally on the other side of the world. The Marine Corps, in helping to answer this question, infused the RDF with its ideas of strategic mobility and readiness, and in so doing, endeared itself to the administration.

As the RDF took shape in the fall of 1979, Marines were reluctant to participate. As they saw it, they already provided policymakers with such a force. Many Marines considered it yet another attempt by the other services, mainly the Army, to usurp one of the Marine Corps’ primary missions. Attitudes shifted quickly, however. In a speech to a group of retired officers, Commandant Barrow described the situation:

Now there are many people who said, why do we need another Rapid Deployment Force – isn’t the Marine Corps a Rapid Deployment Force? I even succumbed to a little bit of that thinking myself. Again, it became apparent that standing off on the sidelines and throwing rocks at it would not kill it if indeed it needed to be, but we were going to have something called a Rapid Deployment Force whether the Marines liked it or not. So then you make a conscious decision, let’s take it over. Let’s kind of ease in there and make it our game.

Some of the Corps’ leading minds provided rhetorical support for increased Marine involvement in the RDF. According to Lieutenant Colonel William M. Krulak, a noted strategist and brother of future Commandant Charles C. Krulak, the service’s success in World War II was due to a singleness of purpose and a clear institutional focus. However, it was time for change. The amphibious assault, a form of warfare better-suited to the sands of Pacific beaches, was no longer relevant to the current strategic environment. To persuade his fellow Marines, Krulak relied on media reports as well as Secretary Brown’s FY 1980 budget testimony in favor of increased funding for non-European contingencies. Embracing the RDF mission would be an evolutionary development and ensure the long-term viability of the Marine Corps. It was imperative that the Marines “take positive steps to become the cutting edge of the Rapid Deployment Force…[it] is an idea whose time (and dollars) has come.” This was the type of mission that would free up funds, seeing as it “is considered vital to national defense, and to the degree that the force levels justified for it can be determined, the resources necessary to support it become valid claimants on defense dollars.”

General Paul X. Kelley (USMC History Division)

Once the Marine Corps’ leadership embraced the RDF mission, the service proved well-suited to the task at hand. In the process of developing the military capabilities to back up the administration’s strategic commitments, the Corps endeared itself to policymakers due to its actions in five areas. First, Marines believed in the mission. As mentioned above, senior Marines were in lock-step with civilian policymakers regarding the importance of oil to the world economy and the need for an intervention force to ensure its flow. The vocal support of highly decorated veterans was greatly appreciated by the embattled Carter administration, which was often perceived as being weak on defense. Time and again in congressional testimony, interviews, and speeches, Marines echoed the concerns of President Carter, Secretary Brown, and National Security Advisor Brzezinski, often using the same statistics and phrases.

This singleness of purpose had much to do with the Marine Corps being “at a strategic crossroads” in the late 1970s, according to former Marine and senior defense official Bing West. William Odom recalled the other services being reluctant. The Army and Air Force, for example, doubly committed forces to NATO and the RDF and gave the RDF mission a lower priority. In their defense, the Army, Navy, and Air Force had enduring missions in Europe and Asia as well as responsibility for the nation’s nuclear arsenal. Marines, on the other hand, needed a mission and viewed the RDF as vital to their service’s future. Thus, they were far more willing to adapt. Commandant Barrow stressed the relationship between the Marine Corps and the RDF in a package he sent to senior Marines. The packet included Secretary Brown’s speeches along with articles on the RDF and maritime prepositioning; recipients were instructed to share the contents with their subordinates. In his cover letter, Barrow explained,

Since the Persian Gulf crisis erupted, there has been an increased interest and growing recognition of Marine Corps capabilities. Because of our readiness and ability to deploy quickly to the scene of a crisis, we can expect to assume an even greater role in the defense of our nation in the years ahead. The major role given to Marine forces assigned to the Rapid Deployment Joint Task Force (RDJTF) already affirms this…I view the decade of the 80s as an opportunity for our Corps to demonstrate its unique capabilities to the Nation and make a significant contribution to national security.

Its enthusiastic support for the mission led the Marine Corps to devote considerable intellectual effort to the problem of projecting force into the Middle East. For example, a list of studies sponsored by the Advanced Amphibious Study Group in the late 1970s indicates that the vast majority dealt with Middle East issues, such as the suitability of landing beaches in Kuwait, evacuating civilians from the region, the challenges of forcible entry and so on. While the Army and Air Force were preparing for war in Europe, the Marine Corps focused its planning efforts and training on desert operations.

Second, the Marine Corps worked closely with administration officials to craft solutions to strategic mobility related challenges. From its inception, the RDF was plagued by deficiencies in strategic mobility, defined as the ability to deploy and sustain military forces over great distances in support of policy objectives. Few areas of the world are further from the United States than the Persian Gulf. The tyranny of distance was compounded by the relative austerity of the theater and the lack of bases in the region; desert warfare is logistically intensive and requires vast supply networks to support operations. On strategic mobility, P.X. Kelley commented: “To the best of my knowledge, we have never, in 205 years of our history, attempted to rapidly project and sustain a force as sizable as the RDJTF over such vast distances. In contrast, Vietnam involved a relatively slow, incremental build-up over years – not days or weeks.” Nevertheless, for the RDF to support policy objectives, it needed to be able to get to the region in question and operate effectively there.

Headquarters Marine Corps made good on its promised readiness and strategic mobility by working with civilian officials within the DoD to bring the Maritime Prepositioning Ships (MPS) Program to fruition. The program, initiated in late 1979 as part of the Five Year Defense Plan, involved loading military equipment and supplies on government-owned, but civilian operated, cargo ships and prepositioning them in the vicinity of potential trouble spots. In the event of a crisis, Marines could be airlifted to the region, marry up with their gear, and conduct combat operations within a matter of days. By 1984, the Maritime Prepositioning Force (MPF) consisted of three squadrons that each carried enough equipment and supplies to support three 16,000-man brigades.

Third, Marines stressed that the geography of the region was particularly well-suited to amphibious forces. Much of the region was accessible by sea and it included two of the world’s most strategically important waterways, the Suez Canal and the Strait of Hormuz. Furthermore, political and cultural concerns precluded permanent U.S. garrisons and made coordinating overflight and basing arrangements difficult. Amphibious forces, on the other hand, offered flexibility and a light footprint. Unlike in Europe and Korea, in the Middle East U.S. policymakers could not be certain where the next crisis would take place, and thus flexibility was at a premium. Moreover, the forcible entry capability of amphibious forces was essential to the RDF and MPF concepts. There was no guarantee that friendly ports and airfields would be available where and when they were needed. If necessary, Marines could seize the infrastructure needed to introduce follow-on forces.

Fourth, the Marine Corps’ expeditionary mindset and emphasis on readiness was directly applicable to the rapid deployment mission. As the name indicates the intent for rapid deployment forces was that they move quickly. General Barrow stressed the Marine Corps’ readiness to fight on short notice:

[Readiness] is our bread and butter in the Marine Corps. It is our credibility with the American public and with Congress that we are to be ready as a state of mind… We are ready in the truest sense of the word… within minutes we could put forces in motion. Ready to go quickly to the points of embarkation and ready to fight at the other end.

Barrow’s claims were supported by Department of Defense readiness ratings that were calculated on the basis of four criteria – personnel, amount of equipment, quality of equipment, and training. At the time the RDF was established, 70 percent of Marine Corps units were rated as combat ready as compared to 37 percent for Army units. One analyst described the Army’s condition as “pervasive operational unreadiness.” Furthermore, all Army units assigned to the RDF for planning purposes were already earmarked for NATO contingencies. In order to fight the Soviets, most of these units were tank-heavy and rather slow and ponderous in terms of strategic mobility, so slow that Senator Sam Nunn joked that the Army’s attempt at a “fast-deployment force…should be more appropriately called the last deployment force.” By comparison, General Barrow told Congress that the entire Corps was ready to support the RDF if ordered.

Finally, the Marine Corps past experiences and basic organizing principle, air-ground task forces – were ideally suited to joint operations. As stipulated by Secretary Brown, the RDF was to include representation from all four services. For most of their histories, the Army and Navy existed in relative isolation from one another. The Marine Corps acted as something of a bridge with a foot in both camps. General Kelley, a well-respected officer who served two tours in Vietnam as both a battalion and regimental commander, was unusual, in that during his career he had served tours with the Army, Navy, and Air Force.

Kelley stressed the importance of joint operations from the outset. Upon taking command of the RDF, he defined the mission of his headquarters as follows:

…to plan the employment of designated forces, to jointly train and exercise them, and to ultimately deploy and employ them in response to contingencies threatening U.S. interests anywhere in the world. In essence, to provide the essential command and control that will bring together, in a synergistic way, the capabilities of the four services.

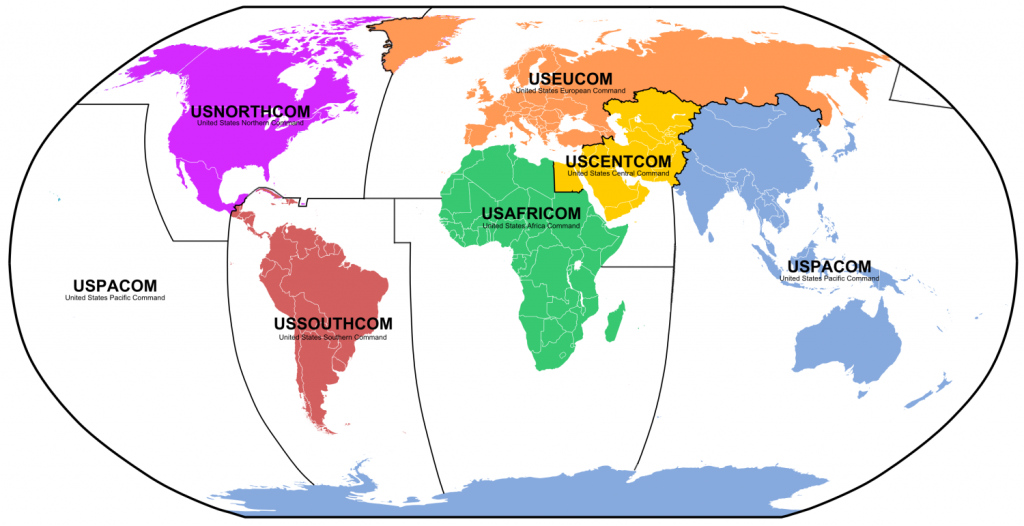

Previously, no single commander had been responsible for U.S. military activities related to the Middle East. The Unified Command Plan, the document that divides the world into different areas of responsibility and assigns them to commanders, split the Middle East region between European Command, typically headed by the Army; and Pacific Command, a Navy run organization. The Middle East was not a top priority for either command. Furthermore, had responsibility been given to the Army or Navy, it most likely would have led to allegations that one was trying to gain an advantage over the other. Placing a Marine in charge, it was hoped, would minimize inter-service squabbling.

From the outset, it was intended that the RDF be much more “joint” than the other commands. According to General Kelley, the RDF was “the only group in this country whose current, fulltime activities focus on joint and combined combat operations.” Along these same lines, Marine General George Crist, Commander in Chief, United States Central Command, the successor organization to the RDF, described his mission as driving “different communities to work together until they come up with joint procedures that produce a cohesive team.” In light of the distances involved, it was imperative that the services cooperate to achieve policy objectives in the region. Of the services, the Marine Corps was arguably the best prepared to lead such an effort.

Moreover, General Kelley organized the RDF in accordance with MAGTF principles. He insisted that air and ground elements as well as the service components plan and train as a team. As Kelley was fond of pointing out, his headquarters was the first permanent peacetime headquarters with representation from all the services. While all the services contributed to the effort, the Marine Corps’ joint focus played an invaluable role in easing the turbulence associated with forming a new command. In addition, similar to the MAGTF, scalability or the “building-block principle” as Kelley referred to it, defined the RDF from its inception. Scalability allowed for the tailoring of forces to meet different policy objectives, which was exactly what the White House wanted. At the strategic level, the RDF’s value as a deterrent hinged on its ability to integrate and task organize elements of each of the services into a balanced and effective force of combined arms.

By 1981, the Marine Corps had so successfully adapted its capabilities to the challenge that one analyst referred to it as “the core” of the RDF. The part played by the Corps in turning the RDF from concept into reality was appreciated by senior policymakers. In a sense, the sudden need for rapidly deployable forces brought about by the Iranian Revolution and Soviet takeover of Afghanistan led to what General Barrow referred to as a rediscovery of the Corps. Secretary Brown, who was known to joke about not needing a Marine Corps in 1977 and 1978, asked Congress to increase the service’s budget in late 1979. By embracing the RDF mission, the Marine Corps benefited significantly from the spending associated with it.

In late 1979, President Carter submitted his first spending requests that represented real increases in military spending; most of the increases targeted Persian Gulf issues. Arnold Punaro, a Marine reservist and legislative aide to Senator Sam Nunn, noted that the Corps was slated to get the bulk of the funding associated with the rapid deployment mission. He went on to say that due to its capabilities in this regard, “The Marine Corps is the force for the Eighties.” In the end, the service avoided a planned manpower reduction and its budget grew by 10 percent in FY 1981 and another 30 percent in FY 1982. The Marine Corps’ newfound strategic purpose, and the spending associated with it, led General Barrow to predict the 1980s would be “a kind of golden era” in comparison to the mid-1970s. Along these same lines, one analyst wrote, “…the USMC has been given a new lease on life, largely because of public concern over the ability of U.S. military forces to deploy rapidly and fight in potential trouble spots around the world.” By 1980, even Jeffrey Record admitted that the Marines had made enormous progress since his Bookings study four years earlier.

Conclusion

On January 01, 1983, the RDF officially became Central Command (CENTCOM), a permanent unified combatant command. Although there were initial growing pains, an astonishing increase in power projection capabilities had been achieved in less than a decade. The Gulf War of 1990 to 1991 demonstrated the dramatic increase in strategic mobility achieved by the Marine Corps and validated the Maritime Prepositioning Force (MPF) concept. Iraqi forces invaded Kuwait on August 2, 1990. On August 7, the 1st MEB in Hawaii, the 7th MEB in California, and the 4th MEB in North Carolina were alerted for possible deployment. On August 8, MPS Squadron 2 sailed from Diego Garcia and MPS Squadron 3 sailed from Guam. On August 12, the first of 7th MEBs 17,000 Marines boarded passenger planes with nothing but their individual equipment. Less than two days later, on August 14, members of 7th MEB began unloading their gear from MPS Squadron 2 at the port of Al Jubayl, Saudi Arabia. By August 20, ground elements of the 7th MEB occupied initial defensive positions and on August 25, the 7th MEB was fully operational. The Marine Corps, assisted by the Air Force and Navy, had moved 17,000 Marines 12,000 miles, their vehicles and supplies 2,800 miles, and integrated both into a combat-ready formation in less than two weeks. The Marine Corps’ high state of readiness was evidenced by the fact that it provided the first combat-ready brigades without having to call-up a single reservist. The service’s contribution eventually totaled 92,990 personnel, 372 aircraft, 268 tanks, 532 amtracks, 302 LAVs, and 216 artillery pieces, making Desert Shield/Desert Storm the largest operation in Marine Corps history.

Central Command AOR

Never before had the Marine Corps moved so many men and so much equipment so far so fast. Former Commandant Barrow credited maritime prepositioning: “the MPS was probably the number one star in the early days of the Desert Shield operation.” The 7

th MEB had established itself in a matter of days. All subsequent units build-on it through compositing. Furthermore, it had only taken two days for the lead elements of the 7

th MEB to get from the West Coast of the United States to their equipment in Saudi Arabia. By comparison, the 4

th MEB, embarked aboard Amphibious Ready Group Two, took three weeks to sail from the East Coast to the Gulf of Oman. If not for the MPF program, the entire Marine component would have had to rely on sea transit. According to Colonel Turley, MPF in Desert Shield demonstrated that “closing times to almost any point on the globe could now be achieved in five to seven days from the notice to deploy.” In 1979, Headquarters Marine Corps had firmly committed the service to the rapid deployment and prepositioning mission. The Desert Shield deployment made this decision appear remarkably prescient in hindsight.

Although the formation of the RDF was a collective endeavor involving civilian officials and all four services, the Marine Corps’ contributions proved instrumental in bringing the project to fruition. Over time, the strategic relevance of the Marine Corps grew along with the importance of the RDF and CENTCOM. At the time the RDF was formed, the services agreed the command’s top position would be filled by Army and Marine generals on a rotating basis. The command thus provided a stepping stone to positions of greater influence for senior Marines. Prior to 1980, Marines simply did not serve in top positions. Thirty years later, they are arguably overrepresented in strategic-level policymaking, having served as Chairman and Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and as combatant commanders on eight separate occasions.

In terms of U.S. foreign policy, the events described above sheds light on an important post-Vietnam debate. As a result of the Vietnam War, Americans were deeply divided over the role of military force in their country’s foreign relations. On one side, were those who believed the war had been a mistake, an example of what can occur when military solutions are offered for problems that are fundamentally political or economic in nature. Simply put, intervening in another nation’s affairs was morally wrong. On the other side were those who felt the war had been a noble cause, one that had deserved the full support of the American people. In their opinion, the national interest was best served by a muscular foreign policy and a willingness to use force abroad. For the former, what became known as the Vietnam Syndrome was a positive development; policymakers should be reluctant to intervene militarily. For the latter, the Vietnam Syndrome was something to be overcome; America’s commitments must be backed by military force.

Activist and author Michael Klare, one of only a handful of outspoken critics of the RDF, argued that its formation marked the end of the Vietnam Syndrome. Although most senior Marines in the 1970s had served in Vietnam and were in some way dissatisfied with American strategy, their attitudes toward the RDF supported Klare’s argument. They viewed military interventions as essential components of foreign policy. One major wrote that it was a “truism” amongst his fellow officers that timely interventions had a “deterrent effect.” For his part, General Barrow held that arguments against ready forces were “the ultimate in ridiculousness,” similar to doing away with fire departments under the misguided notion that fires would just go away. On the military necessity of a “pre-emptive strategy,” General Kelley averred that “once you get a force into an area that is not occupied by the other guy, then you have changed the whole calculus of the crisis, and he must react to you, and you not to him.” The general also subscribed to the notion that the Third World was America’s to win or lose. Success would at times require firm military action. To do otherwise would be to “let it [the Third World] slip through our fingers.”

While the question of whether or not rapidly deployable forces deter or escalate conflicts continues to be hotly debated, what is clear is that the Marine Corps played a central role in making such forces a reality. As one Marine turned historian put it, although policymakers made the decisions to intervene, “[t]he Marines’ force-in-readiness was a fundamental enabler of that habit.” For good or ill, the United States “kicked” the Vietnam Syndrome as President George H.W. Bush put it; and it was due, in large part, to the efforts of the U.S. Marine Corps.

The events described above also highlight the importance of oil in U.S. foreign policy. Concerns over Middle East oil supplies led directly to a shift in strategic priorities. Stability in the Middle East was put on par with the security of Japan and Western Europe. The Carter Doctrine committed the United States to use force to ensure the flow if Persian Gulf oil. The creation of the RDF, the military instrument needed to back Carter’s commitment, was a radical shift in U.S. military strategy and one of the most significant events in U.S.-Middle East relations in the past thirty years. Prior to the RDF, President Franklin Roosevelt was the only president to authorize combat operations in the region. By contrast, every president from Reagan to Obama has found cause to do so.

Although it is easy to find fault with policymakers for failing to foresee the pitfalls of their Middle East strategy, it is important to remember that the creation of the RDF enjoyed not just the wholehearted support of the Marine Corps, but the general public as well. The need for an RDF inspired very little debate; in light of the events of 1979, it was taken as a given. Those debates that did take place were over how strong to make it. The reason the RDF went from concept to reality in only a few months was because a general consensus formed around the need for enhanced military capabilities in the Middle East. The Carter administration’s security initiatives were endorsed by congressmen on both sides of the aisle, as well as military leaders, and were later adopted by the Reagan administration. As one congressional staffer described it, everything about U.S. security policy changed after the Iranian Revolution and the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan. With hostages appearing on the news every night, gas prices rising, and Soviet forces in Afghanistan, the American people believed their way of life and American prestige was being threatened and they demanded action. Thus, the RDF highlights the link between domestic politics and the nation’s foreign policy.

From the end of the Vietnam War through early 1979, the Marine Corps went through a period of intense outside criticism and institutional soul-searching. While great effort was put into justifying its existence, were it not for turmoil in the Middle East, the Marine Corps most likely would have been reduced in size. In the event, national security objectives changed and the Marine Corps’ leaders matched their service’s capabilities to the new challenges. By playing a leading role in the RDF, the leadership of the Marine Corps ensured the service’s continued strategic relevance and the funding that came along with it. In the end, the institution had to adapt in order to survive. Marines entered the 1980s with a clear strategic focus. They knew they were the nation’s force-in-readiness and that the Middle East was the most likely theater.

(Return to July 2015 Table of Contents)

Nathan Packard received a B.A. in history from the College of the Holy Cross and completed his Ph.D. in History at Georgetown University. He is on the faculty of the Naval War College as a Fleet Professor and serves as a reserve officer in the U.S. Marine Corps. He was awarded the Society for Military History’s First Manuscript Prize and the Secretary of the Navy Innovation Fellowship in 2015.

Nathan Packard received a B.A. in history from the College of the Holy Cross and completed his Ph.D. in History at Georgetown University. He is on the faculty of the Naval War College as a Fleet Professor and serves as a reserve officer in the U.S. Marine Corps. He was awarded the Society for Military History’s First Manuscript Prize and the Secretary of the Navy Innovation Fellowship in 2015.